Who was Nino Frank?

A Life in the Shadow of Noir

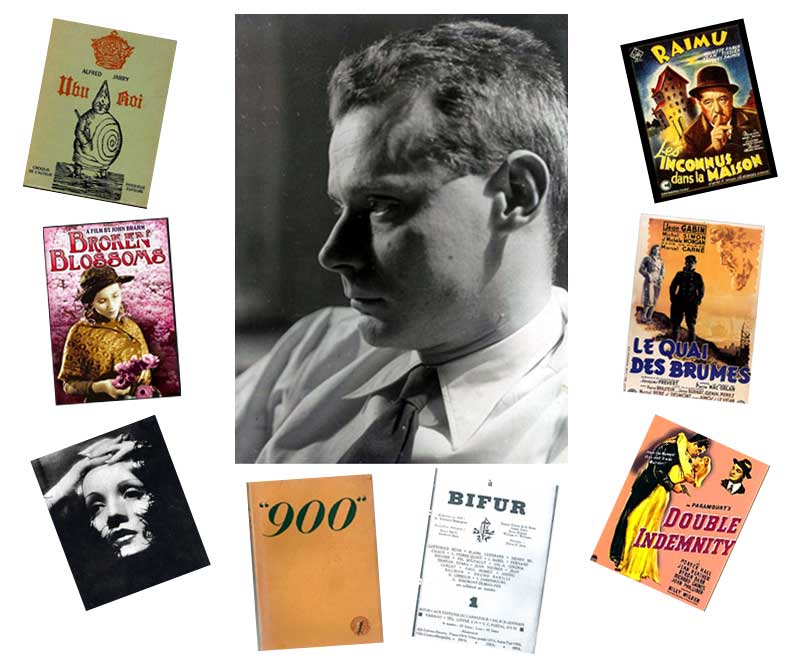

The writer and critic Nino Frank was born in 1904 in Barletta, Puglia, in the far south of Italy, moving to Paris in the 1920s. He and his contemporaries across Europe grew up in what they would see as an increasingly mad world – corrupt, unfair, disorganised. Many young intellectuals would rail against authority, laugh hollowly, and seek out older writers also expressing their disgust through what would come to be called ‘humour noir’.

This humour went way beyond a joke, its purpose was deadly serious: Frank later described it as concerned with “les entités suprêmes que sont l’amour, la terreur, le désespoir et surtout la mort” [‘the driving forces of life: love, terror, despair and especially death’]. As a very young man he was drawn to such writers: to Alfred Jarry and his iconoclastic play Ubu Roi; to Pierre Mac Orlan and his writings, among them Le Rire jaune, about a deadly laughing plague; to Dada and Surrealism; and to the ‘magic realism’ of Massimo Bontempelli.

And he lived with another shadow at the back of his mind. There was hardly a decade of his life when he did not suffer a life-threatening illness: aged 6, he almost died of typhoid fever; at 14, he only just survived Spanish flu; at 15 (perhaps a lingering after-effect of the flu) a dose of pleurisy which knocked him unconscious for three weeks. Minor lung troubles throughout his twenties, culminating at 30 in hospitalization in a Swiss TB sanatorium, for three years. At 44, a major lung operation from which he barely pulled through; at 51, a kidney stone removal which went wrong. As a radio interviewer said to him, “Vous avez côtoyé la mort” [‘You have walked with death’].

As the frivolity of the later 1920s receded and the disastrous direction of the 1930s became clear, French film directors joined the warning voices, in films which would be labelled ‘noir’ by official bodies wishing to minimise any sense of French weakness. In fact, this term was applied to the whole serious movement of ‘social’ or ‘poetic’ realism in French film. Even the highly esteemed Jean Renoir was lambasted in 1939 for the anti-war film La Règle du jeu. Feeling betrayed, he left France.

Thus in 1946 the new seriousness French critics saw in certain Hollywood crime dramas was not new to them: the only surprise was to see it in American films. And it was Nino Frank, immersed as he was, through his life and his reading and his friendships, in the whole sensibility of noir, who articulated the realisation that these films were made in the tradition of ‘films noirs’.

This website is the fruit of several years' research in libraries in Paris, London and Rome, and of conversations with people who still remember Nino Frank. I hope you find it of interest.

Margaret Holmes

QUICK LINKS...

Nino Frank: A Brief Summary of his Life and Work > >

* * * * *

Nino Frank and:

Aged 19, Nino Frank travels from southern Italy to France, meeting Max Jacob, Jean Cocteau and Pierre Mac Orlan. He publishes articles on French avant-garde writers in Il Mondo, and on Massimo Bontempelli and ‘magic realism’ in Paris-Journal.

1926, Nino Frank is appointed Paris correspondent of the Corriere della Sera. Massimo Bontempelli also recruits him to help launch and run his new international journal, “900”. The first issue is a success, with an impressive list of contributors.

Nino Frank tries to smooth over problems with “900” caused by the antagonism of Giuseppe Ungaretti. Bontempelli’s co-editor, Curzio Malaparte, objects to the journal’s anti-fascist tone and content, and contrives Frank’s expulsion from Italy.

4. The magazine Nouvelles litteraires

4. The magazine Nouvelles litteraires

Desperate for work, Frank is helped by Pierre Mac Orlan, who introduces him to Georges Charensol at Les Nouvelles littéraires. There he develops his pen-portraits of literary celebrities, among them Jean Cocteau, François Mauriac and Scott Fitzgerald.

5. The modernist journal Bifur

5. The modernist journal Bifur

Frank becomes assistant editor of Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes’ new modernist French journal Bifur, which features important international contributors: in the first issue, among others Gottfried Benn, Blaise Cendrars, Tristan Tzara, Ilya Ehrenberg.

Frank works for the key film magazine Pour Vous from its launch, and is editor-in-chief at its forced closure in 1940. As a junior, he interviews directors like Jacques Feyder and René Clair during heated debates in France on the new talking cinema.

7. The newspaper L'Intransigeant

7. The newspaper L'Intransigeant

In 1931, as editor of the cinema page of L’Intransigeant itself, Frank expresses his views on the role and responsibilities of film-makers. He is deeply shocked by a visit to Berlin in 1933, and points to warnings in films like Fritz Lang’s Dr.Mabuse series.

8. Welcome back to Pour Vous, 1936

8. Welcome back to Pour Vous, 1936

After a forced absence with tuberculosis, Frank returns full-time in 1936 to Pour Vous and L’Intransigeant, resuming his trenchant reviews. A central theme is how to show the reality of Paris, often a sentimentalised “star” of French and foreign films.

9. 'Poetic' realism in French cinema, 1936-1939

9. 'Poetic' realism in French cinema, 1936-1939

In 1936, an impressive batch of French films leads critics to hail a new realism and concern for social issues. Films of Renoir, Duvivier and Carné are complemented by the acting of Jean Gabin and the poetic inspiration of writer Jacques Prévert.

10. Cinema under the German Occupation

10. Cinema under the German Occupation

After the forced closure of Pour Vous, Frank writes on films at Les Nouveaux Temps; French production is constrained by censorship, but he continues campaigning for quality. In 1942 he is forbidden to write in the French press and turns to scriptwriting.

1n 1946, French critics debate American crime films dubbed ‘films noirs’ by Frank. As well as ‘hard-boiled’ source books, influences recognised come from German emigré directors, and from a French tradition of uncompromising literature, taken forward in films by Renoir and Carné. In more recent analysis, James Naremore sees a close link between Frank’s insight and his modernist background.

12. Du “fantastique social” au “film noir” (chapitre français)

12. Du “fantastique social” au “film noir” (chapitre français)

Pierre Mac Orlan s’enthousiasme pour le cinéma, avec sa capacité de concrétiser les peurs urbaines, le “fantastique social”. Ce concept est une influence-clé sur Nino Frank lorsqu’il reconnaît des éléments “noirs” dans des films criminels américains.

13. His importance today in Barletta, town of his birth

13. His importance today in Barletta, town of his birth

Nino Frank, born in Barletta, was famous for his translations of Italian masterpieces into French. As one of Barletta's foremost literary figures, his birth in Palazzo Tresca featured prominently in recent campaigns to prevent the demolition of this important historic building, and ensure its survival.

* * * * *

Nino Frank et Pierre Mac Orlan (Lectures de Mac Orlan)

Nino Frank et Pierre Mac Orlan (Lectures de Mac Orlan)

Pierre Mac Orlan et Nino Frank, 1923-1927, et le conte Une Nuit

Pierre Mac Orlan, Nino Frank et le cinéma: du "fantastique social" au "film noir"

Orfeo Tamburi et Nino Frank: deux Italiens amoureux de Paris

* * * * *

Short stories featured, original texts:

Goût d'égout

Goût d'égout

L'Oreille noire

La Femme de la nuit (début)

Un Coup de foudre

- - - - - - -

Il Mantello rosso

Il Mantello rosso

Samuele Pallas e la sua felicità

- - - - - - -

* * * * *

Detailed list of Nino Frank's Writings, including:

Frank's Translations of major Italian novels into French

* * * * *

My Translations from French Originals:

Séraphine the Obscure

Séraphine the Obscure

(on Séraphine de Senlis) by Nino Frank

2. The Italian journal "900"

2. The Italian journal "900"

6. The film weekly Pour Vous

6. The film weekly Pour Vous 11. The Fascination of Noir

11. The Fascination of Noir