Chapter 10: Nino Frank and cinema under the German Occupation

War!

Within weeks of Le Jour se lève reaching French screens, Europe would be tearing itself apart again, barely twenty years after the end of the War to End All Wars ("La Der des Ders"). Nino Frank was one of the few non-aligned film critics who continued to write during the early years of the war and the German Occupation. This chapter focuses on his perceptions of the films available to French audiences during those years.

"Les derniers beaux jours"

For Nino there would be a final halcyon interlude, which brought with it the challenge of a new literary form, theatrical writing: a new skill which would later be valuable to him for screenwriting, and for radio and TV dramas.

Early in 1939 he read, in translation, the play Jeppe på Bierget (English Jeppe of the Hill, French Jeppe du Mont), by the eighteenth century Danish dramatist Ludvig Holberg. He recognised this play as an expansion of a medieval folktale, touched on also by Shakespeare in The Taming of the Shrew, in the character of Christopher Sly. Essentially, the story relates the misfortune of a drunkard, on whom a trick is played while he is in an alcoholic sleep: he is conveyed to the duke's castle and put to bed in the duke's own bed, robed in his fine nightclothes. When he wakes, totally confused, the duke and his men continue the joke.

Nino was friendly with a group of young men, theatre and film actors and producers, including Jean Dasté, star of Jean Vigo's film L'Atalante. This group wanted to revive the 'théâtre ambulant', theatrical troupes who performed their plays from town to town, a popular form of entertainment in the 1920s. They were looking for an amusing comedy for their ambitious project of putting on performances throughout Burgundy during August 1939. They commissioned Nino to write a comic play based on the plot he described to them, and they all went to Burgundy to perform the play, entitled "Le Buveur émerveillé", with Dasté in the title rôle.

When the text of the play was published in 1948, Nino wrote in his preface:

We shall never forget that burgundian journey, our last happy days, those hours in the sun in a land overflowing with riches, those nights filled with stars and fragrances, so much beauty on the eve of so much wretchedness.... 1 | orig

The months of the phoney war

The reflex action of the French government upon the outbreak of war was to call a 'general mobilisation', leading to 5 million Frenchmen being conscripted: although in the event, hostilities did not seriously begin for several months.

Almost the entire staff of Pour Vous were called up, leaving one or two older writers and Nino Frank: exempt by virtue of his Swiss nationality, but much more pertinently by his history of tuberculosis. He took over as editor-in-chief, and ran the magazine from September 1939 until the Armistice in June 1940, when it was closed down along with its parent paper, L'Intransigeant. News broadcasts became one of the major features: the government had banned as bad for morale most 'poetic realist' films, and few new films were being made or imported, so most reviews were of unchallenging French films or re-releases.

Nino took it upon himself to report on the cinema news bulletins, leaving to other members of staff and freelances, a number of them women, the film reviews, interviews and 'scénarios romancés' which he would previously have written himself. These reports reproduce perfectly the tenor of the bulletins, and indeed their propaganda purposes. He evidently felt that his usual ironic commentaries would be out of place, and presented the news reports very much as they had been shown, so that it is often difficult to see how far they reflected his own opinion of events. But from the following two examples it can be inferred that his opinion of Hitler was personal as much as patriotic, while his praise for the admirable French and English characteristics displayed in the news items was what was required at the time. Thus, upon the invasion of Poland:

The facts speak for themselves, proving beyond possible doubt how inconceivably despicable is this painter and decorator with his crazed vision...on one side the pitiful marionnette with the swastika and his fanatical automatons, on the other, nations who are disturbed and anxious, completely aware of the importance of what is happening, but resolute and united, their faces already lit up with the broad, serene smile of courage and belief in justice. Not in the least boastful: just a belief in right, which knows its strength and will know how to win. 2 | orig

Then, on 8th November, a description of the French front lines:

... infantry soldiers come down from the front line and meet an artillery convoy going up....if the artillery, with their weapons, have the grave, tense faces of men heading towards the line of fire, the returning infantry, who have lived through days of battle, seem equally filled with emotion. Their smiles have a moving quality: these men have had their baptism of fire, and the test has not unsettled them. France's resources of vitality will not reach their limits so soon. 3 | orig

Evidently, he was describing the atmospheres created in the news items: whether literally or with a certain underlying irony it is difficult to tell - as often with his cinema reviews. But from a series of letters written to him by Jean George Auriol during the first months of the war, we can see that he was somewhat conflicted about where his duty lay. The first letter, dated 1st October 1939, congratulates him on being in charge of Pour Vous, and reassures him that there is no question of his being accused of cowardice:

My dear Nino, how delighted I am! How I congratulate you on being at the tiller of our old tub. You can guess, and you know well that I would be the last to accuse you of profiteering and cowardice....At least I hope you are enjoying sufficient freedom of manœuvre and movement. On the other hand, evidently the subject-matter is, if one can say so, less rich than in normal times. 4 | orig

By the 19th, Auriol is seriously concerned that Nino, evidently still troubled by his conscience, is thinking of volunteering, and reminds him that his tuberculosis could return at any moment:

My dear Nino, I must admit to you – given our friendship – that I was stunned by your reckless (or despairing, or affected, or provocative?) gesture. Where will a sense of modesty hide now? or has the cheap serial romanticism of American films made a great baby of you? Finally have you forgotten what application and energy you had to put in to defeat a formidable illness which asks nothing better than to return to the offensive? 5 | orig

And on 10th November, probably after reading Nino's flowery review of 8th November (quoted above), he tells him that if he feels he must follow so closely the line of the news agencies, he should be with Havas (the largest French agency). He describes what life at the Front is really like, and implores him to return to his normal self:

You should be with Havas...! As far as the "life in the open air" goes, which intoxicates your whirling brain-cells, I recommend to you the front line bunkers, the Lorraine clay, the fogs of the Rhine or the Moselle, the snow which is already here, and the stifling atmosphere at headquarters. I beg you, go back to the cinema where your imagination has free rein. You will thank me for this honesty, and this reserve. 6 | orig

In fact, apart from the inconclusive Saar Offensive of September and October 1939 – a brief advance of the French Army into German Saarland, never carried through – no real news would emerge from the "phoney war" until the following May, when the French were defeated at humiliating speed. Thus for around five months, the cinema world would turn in on itself, with the production of anodyne films, the arrival of mainly undistinguished films from America, but still the ever-present Hollywood gossip. Nino would do his best with the material at his disposal, but inevitably these were not the most exciting months in the history of Pour Vous – as Auriol had forecast in his first letter.

When France signed an armistice with Germany in June 1940, publications which might not see eye-to-eye with the Government were immediately closed down. Among these was the high-profile daily, L'Intransigeant, and its film weekly Pour Vous suffered the same fate. Writers employed by these papers were out of work from one day to the next, and opportunities for journalistic work quickly became limited and politically constrained.

Nino Frank looked round desperately, travelling as far as Clermont-Ferrand on a recommendation, but to no avail. In November 1940 he even began to contribute to the women's fashion magazine Pour Elle, writing romantic short stories - but with his trademark sarcastic edge. Fortunately, an interview he had conducted in 1938 would open the way to an offer of more rewarding work, back in film journalism.

Enter Jean Luchaire

In the spring of 1938, the young actress Corinne Luchaire had been filming Prison sans barreaux, directed by Léonide Moguy. Nino arranged to meet her in the Bois de Boulogne, and carry out the kind of chatty interview with photographs which often accompanied the launch of an important film. Then other projects took priority, and it was not until August that he wrote his article, which by then had become a sympathetic profile of Corinne, more than of the film which had made her an up-and-coming star. In essence, the article created a story from the photos which had been taken, each accompanied by an affectionate, humorous comment. Below is the final photo from the article: the two of them together in a limousine borrowed as a 'prop', with Nino's commentary:

Final scene of the tragi-comedy: we were sitting on the front bumper of a sumptuous car (yours? mine? I don't remember what we had decided I would say), you were supposed to act out the heavy yawn of the interviewee wearying of so many "questions". I am still grateful to you for putting so little conviction into your yawn... 7 | orig

Corinne's father, the newspaper owner Jean Luchaire, was charmed by the article. Two years later, with Nino now out of work, Luchaire offered him the job of running the cinema page of his new paper, Les Nouveaux Temps. He was promised complete freedom of action, and from his first article pursued the ambitious and – for the times – somewhat idiosyncratic agenda of demanding that films should aim for psychological depths to equal those achieved in the best literature.

Journalism under the Occupation

Nino Frank returned to film reviewing at a critical moment for French cinema. Ever since the signing of the Armistice in June 1940, France had been in a state of paralysed shock, and investment in non-essential activities was at a near standstill. It was only too evident that any protest, physical or verbal, would not be tolerated, and censorship was imposed not only by the German Occupiers, but also by the Vichy government. Marcel Carné realised immediately that directors would no longer be free to show frank representations of French society, and wrote bitterly in Aujourd'hui at the end of September:

Indeed you will have to adapt, abandon the miserable, anxious face of yesterday, the dreadfully wrinkled one of today. A period of reconstruction demands the positive face of hope – that of youth, and of enchantment.

But even in his despair, he hoped that French directors would manage to preserve, however disguised, "something of the controlled emotion of a Feyder, the passionate spark of a Renoir, the tender irony of a René Clair, or the power of a Duvivier". 8 | orig

By the beginning of November 1940, however, activity in the French studios had barely begun again. Apart from the question of funds, there were other practical difficulties. Many directors, stars and technicians had escaped – while there was still time – to America, or to the Unoccupied Zone in the South of France. Nino wanted to start on an optimistic note, and in his first article for Les Nouveaux Temps he welcomed the opportunity for French audiences to see once again the best European films – especially German, Italian and Russian – after being deprived of them since before the war. Making the best of the situation, he declared that much of French cinema was too slavishly dependent on a Hollywood model which had become stale, but now had the chance to return to its European traditions:

Where cinema was concerned, we were condemned to be nothing but a colony of Hollywood, as if suddenly we had ceased to belong to Europe, to be part of this continent which is our own...now, still cut off from recent or new French films, we are finally getting to know some of the good German productions of the last few years. 9 | orig

The following pages describe the main film events of note, as perceived by Nino, between November 1940 and June 1942, when he left the paper. The full set of his articles in Les Nouveaux Temps can be read on microfilm at the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale, and they provide a fascinating window on to the slim hopes, and the disappointments, of that very difficult period.

German films in France

Apart from a few re-issues of older French films, for the next few weeks Paris cinemas showed almost exclusively German films, and Nino developed a clear strategy for his reviews, against a background of strict censorship. He had a longstanding admiration for some of the German actors known in France since the days of silent film and for iconic early sound films, some made in both German and French versions. There were three actors he admired particularly, who all appeared in two films which arrived in Paris in November: Le Maître de poste [Der Postmeister] starred Heinrich George, and La Lutte héroïque [Robert Koch, der Bekämpfer des Todes] featured Emil Jannings and Werner Krauss. In two related articles he reviewed the two films, giving detailed résumés of the plots and the originals on which they were based (the first on a novel by Pushkin, the second on the true story of Robert Koch, discoverer of the tuberculosis bacillus), and recognising the skills of the director, the scriptwriter, the cinematographer in each case. But at the centre of his appreciation were these key actors, whose contribution he praised at length. Thus:

two of the most noteworthy German films, Gustav Ucicky's Le Maître de poste and Hans Steinhoff's La Lutte héroïque, where we can applaud, in the first, Heinrich George, and in the other, Emil Jannings and Werner Krauss...And although the works merit praise for their style and composition, their greatest interest lies in the interpretation of their rôles by these splendid actors, 10 | orig

and in the second article:

The three great German actors: Heinrich George, or down-to-earth sincerity personified; Emil Jannings, whose characters all seem real, but only real; and finally Werner Krauss, or the master of the indefinable, the complex, the enigmatic... 11 | orig

In this second article he would go even further in his admiration for Werner Krauss, who played the conservative elderly doctor and State Councillor who tried to prevent acceptance of the young doctor's discovery:

his expression has everything – senility, slyness, the profound lethargy of the man who has arrived but is now too old; ferocity, an astonishing dignity, right up to the extreme physical and moral shrinking which happens to certain old men too wrapped up in their own fame. It seems impossible to put more meaning into a rôle, or to go so far in interpreting the inner person. 12 | orig

In February 1941, a German production arrived which it would take all his ingenuity to review without attracting censorship or, alternatively, appearing to approve its denigration of the Jews. For the première of Le Juif Süss [Jud Süss], sponsored by Goebbels, there was effectively a three-line whip on those active in cinema to attend. (Marcel Carné did cunningly manage to claim indisposition and stay away, but he was not making a film at the time.) Nino's article was entitled 'Bas-Fonds', an oblique reference to Gorky's novel and Renoir's film about down-and-outs. He began with a four-column review praising L'Enfer des Anges, a new film by the French director Christian-Jaque, to which we return later. This was followed by two-and-a-half columns on Le Juif Süss.

For this film, he again adopted his strategy of describing the plot but then concentrating on the actors. He explained the actual eighteenth century historical context, of the success of the Jew Süss Oppenheimer at the court of Württemberg, and his eventual downfall; going on to say that the narrative of the film broadly followed the facts, but avoiding any reference to the anti-semitic tenor of the dialogue and angling of the screenplay, other than to state briefly that "upon this narrative, Veit Harlan [the director] has grafted some curious, harsh episodes". 13 | orig He then concentrated on the acting, most especially that of Krauss: the actor who could immerse himself totally in his rôle. In this film, the non-Jewish Krauss had the perfect opportunity to demonstrate this ability, since he played four Jewish speaking parts, all represented as unpleasant or pathetic – the Rabbi Loew, Süss's Secretary Levy, the butcher Isaak and a bearded old man fearful for his daughter – as well as other walk-on parts in the Jewish ghetto. Even among German colleagues, he was accused of excessive enthusiasm in his near-parodic treatment of these Jewish characters, but declared "That's nothing to do with me – I'm an actor." ['Das geht mich nichts an – ich bin Schauspieler'].

In his review, Nino emphasised the actor's incredible ability to take on, so believably, one rôle after another – "He's a whole ghetto, all by himself. What a truly dizzying actor!" 14 | orig He pointed out the contrast between the creepiness of Krauss's Secretary Levy, and the pathos of his elderly Rabbi, Loew. Characterising Levy briefly as "ghastly and ingratiating" ['calamiteux et chattemite'], he described at some length the depiction of Loew, which he found very moving:

his interpretation of the rôle of Rabbi Loew, where you feel more than his skill, more even than his art - truly the creation of a terribly living being, the memory of whom you cannot forget...Rabbi Loew, bleary with age, piping out wise sayings, expert in the stars [he was an astrologer] and in obtaining dispensations from Jehovah; gruff, unsteady, twitching, only half-human, almost a ghost. 15 | orig

French cinema begins to revive

By now, French cinema was beginning to show signs of new life, and more and more the reviews in Les Nouveaux Temps would be concerned with French films, and the French industry. A few films trickled in from the Unoccupied Zone, where production had continued, but in Paris the only real possibility for French directors was to work for the newly-formed German company, Continental. Very quickly, two films were in production, and journalists were invited to the studios. These films were L'Assassinat du Père Noël, directed by Christian-Jaque, and Le Dernier des Six, directed by Georges Lacombe and scripted by Henri-Georges Clouzot.

But the first interesting new release - already noted above – was an earlier film by Christian-Jaque, completed in 1939 but only approved by the censors in February 1941 – L'Enfer des Anges, scripted by Pierre Véry, but with additional input by Jacques Prévert, who had also worked on the director's earlier film, Les Disparus de Saint-Agil. The story concerned vulnerable adolescents at the mercy of a drug dealer, and had been made by Christian-Jaque within the context of the realist films of the late 1930s. It was introduced by the statement:

But the first interesting new release - already noted above – was an earlier film by Christian-Jaque, completed in 1939 but only approved by the censors in February 1941 – L'Enfer des Anges, scripted by Pierre Véry, but with additional input by Jacques Prévert, who had also worked on the director's earlier film, Les Disparus de Saint-Agil. The story concerned vulnerable adolescents at the mercy of a drug dealer, and had been made by Christian-Jaque within the context of the realist films of the late 1930s. It was introduced by the statement:

Ce film expose dans sa cruelle vérité la détresse de l'enfance abandonnée, sans guide, sans défense, sans tendresse dans la vie. 16

There was also a clear link to social-comment Hollywood films of the same period, and in his review of the film Nino specifically mentioned William Wyler's Dead End:

L'Enfer des Anges presents us with a story of abandoned children, interpreted by some astonishing young actors, as picturesque, as alive as those in the famous Dead End and other American films in the same vein: nothing could be more appealing.

Certain episodes, too true to the sordid realities of the slums, had been cut: "If I'm not mistaken, the moralising censorship of Vichy has been at work here." But in the present circumstances this was perhaps to be expected. It was the producers who were the target of his main criticism. Because he viewed this as a serious piece of filmmaking, purporting to face up to injustice and callousness in society, he had a major objection to the ending, which did not ring true. He would voice frequently – and increasingly, as fancy replaced reality more and more in films made under Occupation conditions – this criticism, that producers claimed that they could only sell films with happy endings, thus insisting on falsifying serious stories:

Their story should have ended with death, and loneliness: but because of the wishes of those who trade in films [the producers], it will be a miraculous cure, flowers on the hospital bed, applause, and no doubt the prospect of a marriage blessed with many children...I won't go on. 17 | orig

Then soon afterwards, a French film of an entirely different kind was released in Paris, the first to arrive from the Unoccupied Zone.

La Fille du Puisatier [The Well-Digger's Daughter]

Marcel Pagnol, theatre and film director, already famous during the 1930s especially for his 'Marseille Trilogy' (of films featuring the same characters), Marius, Fanny and César, had begun making a new film, La Fille du Puisatier, in the spring of 1940, but he was not able to complete it until early 1941. Both Pagnol and his critics considered his films to be outside the normal film parameters of the time, and his filmmaking was often referred to as "théâtre filmé". His films often came directly from his stage plays, and contained substantially more dialogue than was approved of by those directors and, especially, critics who felt that the particular strength of cinema lay in its ability to access and manipulate physical images to an extent which was impossible for theatre. Pagnol insisted on the importance of dialogue for exploring human emotional and psychological complexities: with the result that his characters, the people of Provence, were much loved by audiences across the world.

Marcel Pagnol, theatre and film director, already famous during the 1930s especially for his 'Marseille Trilogy' (of films featuring the same characters), Marius, Fanny and César, had begun making a new film, La Fille du Puisatier, in the spring of 1940, but he was not able to complete it until early 1941. Both Pagnol and his critics considered his films to be outside the normal film parameters of the time, and his filmmaking was often referred to as "théâtre filmé". His films often came directly from his stage plays, and contained substantially more dialogue than was approved of by those directors and, especially, critics who felt that the particular strength of cinema lay in its ability to access and manipulate physical images to an extent which was impossible for theatre. Pagnol insisted on the importance of dialogue for exploring human emotional and psychological complexities: with the result that his characters, the people of Provence, were much loved by audiences across the world.

In his review, on 26th April, Nino tackled these critical debates head-on, with two questions: 'Is it a good film?' and 'Is it cinema?' [Que vaut ce film? Est-ce du cinéma?] This last question had been at the heart of furious discussions ever since the beginning of talking cinema, with the advocates of silent cinema ("le cinéma pur") resisting the use of dialogue altogether, claiming that cinema was an art of images. Nino's own words explain both the dispute and his personal opinion of Pagnol and his films:

Is it cinema?

Who still recalls the quarrel that some people picked with Marcel Pagnol, a few years ago? This author, leaving the theatre, declared that in future he would devote himself to the cinema; and, as a dramatic author, he stressed the fundamental importance of the text, going so far as to show a certain disdain for the special contribution made by the moving images. People attacked him, argued with him, criticised him. And meanwhile, Marcel Pagnol made César, Angèle, yesterday La Femme du boulanger, today La Fille du puisatier. In all these films, as Marcel Pagnol had always asserted, the text formed the basis of the work: but the author also made every effort to animate and vary the images, like the most orthodox of directors. And that created excellent cinema – for a hundred theoretical discussions are not worth a good film, and a man like Marcel Pagnol could not fail to make good films.

He went on to explain his own assessment of the new film:

La Fille du puisatier is probably not a 'chef-d'œuvre'. But it is indeed an 'œuvre'; and cinema produces hardly any, anywhere in the world, which keep us thinking about their significance, which offer us something more than agreeable images, which, in short, ennoble through their sincerity this industry of cameras and studio lights...Marcel Pagnol and his actors, you can only compare them to a force of nature: the genius of the author reaches an almost Tolstoyan perfection, so that he writes and composes, as it were, on the level of humanity in its pure and integral state. 18 | orig

The underlying humanity perceived in this film, the emotional and psychological complexities of its characters, are important in the light of the banal plot, a frequent occurrence in French films of the period. The heroine is seduced by a young man (a pilot, in this case) who goes off to the war; she is pregnant, and is thrown out by her father; the pilot is thought to have perished, but finally returns and marries her. In his review, Nino did not deny the banality of the theme, or certain longueurs in the production, but nonetheless, as the quotations show, considered the vital aspects to be its underlying sincerity and humanity, and Marcel Pagnol to be an exceptional director.

Intervention of Henry de Montherlant

In the following weeks, this relatively modest film would form the springboard for a debate about the whole future of the French film industry. In June, the writer Henry de Montherlant wrote an article in the new rightwing journal Lectures, entitled 'Va-t-on laisser mourir la France?' The gist of this article was that the moral fibre of France was in danger, that cinema was a harmful influence, especially on the young, and that films like La Fille du puisatier represented this moral degeneration. And he described Pagnol's film as "un film misérable", "un film abaissant et démoralisant". His proposal, to tackle this unacceptable situation, was:

a body which will protect the "qualité humaine française" [virtually untranslatable, in the context meaning approximately 'quality of the French character'], with a will for intransigence and coercion. A kind of inquisition in the name of the quality of the French character. 19 | orig

Evidently he was calling for cinema to be subjected to rigorous censorship. And given that his declared attitude to the Occupation was:

Do what you can to crush the enemy. But once he has shown that he is the one on the right track, become his willing ally,

it was evident that this would mean a ban on anything subversive, even obliquely, and particularly on any films showing the character of the French people in anything other than a favourable light. 20 | orig

Nino was stung to reply, partly because he and Montherlant disagreed about the value of this particular film, but more fundamentally because Montherlant, who normally took little interest in cinema, appeared to be laying down the law on a subject which had exercised film critics and directors for years. Many efforts had been made to appoint a supervisory body, with the aim of ensuring acceptable levels of technical and artistic quality – but not of censoring subject-matter (other than outright pornography). He replied in the magazine in which Montherlant regularly wrote, La Gerbe, ironically referencing the writer's demand for an 'inquisition', in his title and a number of times in his article. He sketched out the previous (largely abortive) attempts which had been made, and described the current arrangements: a State body in Vichy, which had inherited the censorship powers previously held by Edmond Sée, with an Admiral currently in charge (!); and the Comité d'Organisation de l'Industrie du Film, unable to make any decisions without the approval of Vichy.

And he emphasised that the task would need to be undertaken not by a State functionary, but by someone familiar with the world of cinema: professional knowledge was needed to make judgments on the acceptability of film scripts, but there were also much more far-reaching aspects:

...In addition, there is the training of practitioners to oversee, the creation of a centre of studies, like that at Cinecittà, the protection of cinema spaces and cinémathèques [film archives]....Will all that be demanded of admirals and bureaucrats? 21 | orig

The French industry already had a Cinémathèque, thanks to Henri Langlois who had gathered and preserved thousands of films almost single-handedly, hiding many of them from the Germans, but he certainly needed more official support. Sporadic efforts had been made to introduce some training, artistic and technical, but nothing approaching the Italian Centro sperimentale di cinematografia, close to Cinecittà, founded as early as 1935, and much admired. Nino was well aware of it through his contacts with Italian filmmakers.

In the event, a compromise solution was found within the next months. Louis-Émile Galey, who had attended the École des Beaux-Arts and spent much of his youth in the artistic circles of Montparnasse, was desperate for money during the Occupation and was prepared to work for Vichy. He was appointed Directeur-Général de la Cinématographie in 1942, and subsequently also Government Commissioner for the Comité d'organisation de l'industrie cinématographique (thus combining the two previous rôles).

Nino was impressed by early indications of his plans for the French film industry, writing in Les Nouveaux Temps at the end of May 1942, after a disappointing crop of films:

In L.-É. Galey, Government Commissioner for the Cinema, we have a friend, passionate about the art of moving images, who has already given proofs of his good intentions, who is beginning to carry out serious actions in favour of quality cinema, and from whom we can await further decisive efforts to save French film.

And he quoted, approvingly, from an article by Galey in Comœdia:

"Film production in 1941-1942 was poor. That of 1942-1943 will be rather better. It could be good, if the producers gave more attention to their work and surrounded themselves with more talent....How many producers still consider a film like some kind of grocery product, that you put together in a rush and sell off from one day to the next...I don't want it to be like that in future. I have too much confidence in my country to doubt that people will listen to what I say." 22 | orig

While treading carefully within Vichy restrictions, Galey did encourage the making of films of high artistic and technical quality – the origins of what became known as the "cinéma de qualité". In 1942 he created the 'Grand Prix du Film d'Art Français', the precursor of the film prizes at the Cannes Festival. He helped and encouraged the Cinémathèque, and enabled Marcel l'Herbier to open the training school IDHEC. At the Liberation he was subjected to questioning, but absolved of any blame for his connections to Vichy.

Henri-Georges Clouzot

In the early 1930s, H.-G. Clouzot had been recognised as a talented scriptwriter, but subsequently he spent many years in and out of tuberculosis cures. In early 1934 he had the room next to Nino Frank in the sanatorium at Leysin, where they had chatted together for hours on end. So Nino was particularly cheered at his return to the film world, had been happy to be invited on the set of the film Le Dernier des Six, for which Clouzot had written the script, and waited with impatience for the film's release, in September 1941. He was now working as a critic on an additional publication, the film and theatre weekly Vedettes, where he decided to write a substantial review of the film.

In the early 1930s, H.-G. Clouzot had been recognised as a talented scriptwriter, but subsequently he spent many years in and out of tuberculosis cures. In early 1934 he had the room next to Nino Frank in the sanatorium at Leysin, where they had chatted together for hours on end. So Nino was particularly cheered at his return to the film world, had been happy to be invited on the set of the film Le Dernier des Six, for which Clouzot had written the script, and waited with impatience for the film's release, in September 1941. He was now working as a critic on an additional publication, the film and theatre weekly Vedettes, where he decided to write a substantial review of the film.

It was a detective film from a story by the well-known Belgian writer S.-A. Steeman, scripted by Clouzot, directed by Georges Lacombe, and starring Pierre Fresnay and a new young actress, Suzy Delair. The plot was rather creaky, but Nino chose to leave his criticisms to the end and concentrate first on unstinting praise of all these contributors, starting with Clouzot:

Definitely, Henri-Georges Clouzot is establishing himself as one of our best scriptwriters and one of our best writers of dialogue: his talent is supple and rich, his skill is boundless...After a long absence from the studios, he has returned to us with new good evidence of his know-how...Let us applaud Henri-Georges Clouzot, 23 | orig

followed by the director:

Georges Lacombe has been able to give it a rapid and lively rhythm, which has the spectator holding his breath, and scrupulously respects the conventions of the crime film,

and the key actors:

with Pierre Fresnay in the lead who, in one of these traditional rôles of phlegmatic and mocking police inspectors, enchants the spectator through the richness of his interior play, the humour of his attitudes and of his way of talking...Suzy Delair who, personifying a stuck-up young madam, with a caustic wit, a character which is undoubtedly a bit superficial, stakes out her ravishing and comical authority,

even going so far as to compare these actors with the famous Hollywood married couple from the Thin Man series:

a French film-detective couple, in the tradition of the famous Myrna Loy and William Powell.

But after praise for the contributors to the film, the reviewer had "grandes réserves". For some years he had been criticising the facile nature of detective films and the fact that they were just intellectual puzzles: one of the reasons for the enthusiastic welcome he would give to the first American "films noirs" in 1946, which appeared to relate to real life, however sordid. And here he felt that even the plotting of the detection was less than credible:

We pity the worthy commissioner Wens for not discovering the murderer right at the start, which everyone could do who knows a bit about this kind of work and about the facile tricks used by authors lacking in imagination. 24 | orig

Jean Grémillon's film Remorques

As we have seen, during 1941 critics were becoming increasingly disillusioned with the quality of recent French films, which were handicapped as much by the exodus or disappearance underground of many of the best cinema talents, as by lack of money and the demands of censorship. In December, Nino was therefore very pleased to be able to review a film by the eminent director Jean Grémillon, Remorques, made but not quite finished in 1939, and starring Jean Gabin, Michèle Morgan and Madeleine Renaud, with dialogue by Jacques Prévert. It was like a return to French cinema's glorious years in the 1930s.

As we have seen, during 1941 critics were becoming increasingly disillusioned with the quality of recent French films, which were handicapped as much by the exodus or disappearance underground of many of the best cinema talents, as by lack of money and the demands of censorship. In December, Nino was therefore very pleased to be able to review a film by the eminent director Jean Grémillon, Remorques, made but not quite finished in 1939, and starring Jean Gabin, Michèle Morgan and Madeleine Renaud, with dialogue by Jacques Prévert. It was like a return to French cinema's glorious years in the 1930s.

Still writing in Vedettes, he gave fulsome praise to this film:

This lovely surprise: an ambitious work full of pathos, a magnificent film...let us thank those who took the initiative of completing this film and giving it to us today, in its robust and moving simplicity, in its simple truth.

In fact, the film bore all the usual hallmarks of Grémillon's work: the setting was very dramatic – the tugboat pitted against the Atlantic sea – and the story was one of doomed love, with the melodramatic addition of an invalid wife prepared to sacrifice her own happiness for that of her errant husband. Clearly the believability of the film would depend very heavily on the skill of the actors, and the husband's rôle was tailormade for Gabin:

Rarely had Jean Gabin found a rôle which brought out his talents as well as this one in Remorques... It's clear to see.

Indeed, the critic concentrated his praise on the way Grémillon and his team had succeeded in bringing out the best in all the actors, and making the story seem credible and true. Thus Michèle Morgan rendered believable

the lost soul who appears just long enough to recover hope, then disappears again, and her innocent pathos is one of the shining lights of this film,

while Madeleine Renaud was entirely convincing as "an unhappy woman who humbly sacrifices herself, right up to a death without fuss". 25 | orig

Nostalgia for the days before the war is heavy in this review. Nino could not resist devoting a paragraph to one of the minor members of the cast: Jean Dasté, "the excellent Jean Dasté". The film had brought back to him a flood of memories from 1939 and the performance of Nino's play "Le Buveur émerveillé" (discussed at the start of this chapter). Already at that time Dasté had declared that Remorques would be an impressive film. And Nino, wistfully, in this pitiless winter of 1941, re-lived the summer of 1939:

Do you remember, Jean, our wanderings from village to village, with that play? You were the first to say to me, in front of our jugs of Meursault, that Remorques would be a splendid work. That must have been on 15th August, 1939. Ten days later, you exchanged your "Buveur émerveillé" rags for your uniform. 26 | orig

Significant films in early 1942

During the first half of 1942 at Les Nouveaux Temps, Nino found only three films which roused his enthusiasm sufficiently to justify full-scale reviews, evidence of his continuing disillusionment with French cinema under the current circumstances. These all boasted a well-known director or writer from an earlier generation, all much admired by the columnist, who clearly also wished to promote the work of his old friends.

La Piste du Nord

On 21st March, he had the pleasure of reviewing a newly-released film, made in 1939 by his idol Jacques Feyder, with dialogue by Alexandre Arnoux: La Piste du Nord (now lost). This film does not feature today in the list of Feyder's greatest successes, perhaps because its plot - a crime of passion followed by a pursuit in the wastes of the Canadian North - was unusual for Feyder but also very difficult to shoot outdoors in winter in the Swiss Alps, or to reconstruct in the studio. While recognising this, Nino was bowled over, as he always had been, by the brilliance of Feyder's style, and concentrated in his review on this aspect of the film:

At the present moment, in Europe, we never see a director capable of making an ambitious work in such an original and dazzling style...in spite of its imperfections, it certainly seems that La Piste du Nord should be ranked highly in Jacques Feyder's work: if it does not have the elegance and the finish of La Kermesse héroïque, the bitter pathos of Thérèse Raquin or the dynamism of Le Grand Jeu, it is characterised by such high quality in the style, especially in the first part, such masterly restraint in telling the story, but especially a moral content of a pure nobility that we no longer expected to find in works for the screen, that it would not be out of place to look within it for a spiritual message from one of the rare artists of the cinema. 27 | orig

La Duchesse de Langeais

Two aspects gave particular interest to this film, reviewed on 4th April. It was the first occasion on which the long-admired novelist and playwright Jean Giraudoux had written the script for a film, in this case directed by Jacques de Baroncelli, with music by Francis Poulenc. The film was an adaptation of a short novel by Balzac, from his volume L'Histoire des Treize, which Nino dismissed as "qui n'est point ce que Balzac a fait de mieux". Nonetheless, it appears that many commentators had criticised Giraudoux for departing from Balzac's plot, and Nino decided to use his review to defend the writer's choices. He did this not only because in his opinion they improved the film cinematographically speaking, but also in defence of the principle that the two media required different plot choices and treatments.

This decision had the effect of concentrating the review on plot differences between the two works; but more interesting is the challenge it contained to other critics, and Nino's passionate belief in Jean Giraudoux and the very personal contribution he could make to cinema:

this film is less an adaptation of Balzac's famous novella, less Jacques de Baroncelli's achievement, than a new work by Jean Giraudoux, an engaging, thrilling story, the kind you hope to get from the cinema....[Giraudoux] a prince of wit and style - a poet. It seems that, without the least hesitation, we should congratulate ourselves that the art of moving and talking images has gained such a talent.

A key problem, in turning the story into a film, was the sparseness of episodes, so that Giraudoux had been obliged to add some inventions of his own. While accepting that certain of these were more propitious than others, Nino was convinced that overall the strategy succeeded:

Thus, the scriptwriter, borrowing from Balzac the characters and the theme, found that he had to invent the twists and turns of the story. Should we reproach Giraudoux for having decided not to pastiche Balzac, but to compose a Giraudoux?....the development of the story becomes much more coherent: even if the rhetoric in Mme de Sérizy's salon is a little too theatrical - but so touching! - the intervention of Ronquerolles at the end makes it easier to explain the event. In its detail, the story holds together better than in the Balzac. 28 | orig

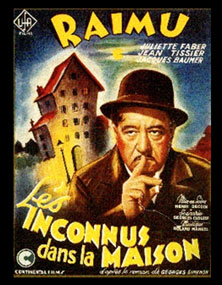

Les Inconnus dans la maison [The Strangers in the House]

This film was directed by Henri Decoin and scripted by Henri-Georges Clouzot, from a novel by Georges Simenon, and starred the legendary French actor Raimu. It can still be bought on DVD today, and is one of the few French films of the period to be marketed with English sub-titles. Henri Decoin was a talented director, whose subsequent reputation suffered from his wartime willingness to collaborate with the German film industry, and to work, as here, for Continental, the German film company in Paris. Clouzot was likewise condemned after the war. But in recent years critics and film-lovers have revisited their films and recognised the artistic talent which went into making them.

This film was directed by Henri Decoin and scripted by Henri-Georges Clouzot, from a novel by Georges Simenon, and starred the legendary French actor Raimu. It can still be bought on DVD today, and is one of the few French films of the period to be marketed with English sub-titles. Henri Decoin was a talented director, whose subsequent reputation suffered from his wartime willingness to collaborate with the German film industry, and to work, as here, for Continental, the German film company in Paris. Clouzot was likewise condemned after the war. But in recent years critics and film-lovers have revisited their films and recognised the artistic talent which went into making them.

This story, very suitable for the mood of deep misery gripping France in early 1942, and filmed by Decoin and his cinematographer Jules Krüger in depressing shades of grey, is of a miserable rain-soaked northern French town, where young people from good homes are so bored that they play dangerous tricks, ultimately causing them to become the suspects when a man is killed. But at the trial the judge points the finger at the respected burghers of the town because they have not invested in providing a stimulating environment for their adolescent children. In true Simenon tradition, he then identifies the criminal, without further evidence, through clever psychological deduction. Very unusually, the director and scriptwriter had decided to introduce the film with a monologue, notionally spoken by Simenon himself, describing the ambiance of the film and providing the background to the plot.

Nino was excited by this departure from usual film practice, and it offered him the opportunity to raise the question, about which he felt strongly, of why - in contrast to all other media - cinema practitioners chose to remain distanced from their characters:

Cinema has been made into the objective, indeed impersonal, art par excellence, although in its basic principles it offered better possibilities than the theatre for the direct expression of an author's thoughts and sensibilities. Those who compose for the cinema hide scrupulously behind their characters, as though these could enjoy an autonomous existence, as Unamuno and Pirandello claimed...But consider the cinema spectator: what he asks from the screen is not an impersonal representation of reality, but a sort of human or poetic message.

....the theatre writer, with fewer resources than his screenwriter colleague, has always tried to involve himself with his characters: the choir in Greek tragedy started out as the expression of the crowd, thus the announcement of the unfolding disaster, but it quickly became a vehicle for the author's thoughts. Every time a poet has worked for the theatre, he has introduced his own voice.

He felt that the choice of Decoin and Clouzot to introduce the voice of the author was an important step forward for cinema, and had proved a success, overcoming the unevennesses in the film:

Les Inconnus dans la Maison is far from being a chef-d'œuvre; and yet I saw the spectators following the course of events with a kind of anguish and applauding at the end, passionately, as if they had just been released from a spell. 29 | orig

In this article he also mentioned Sacha Guitry's 1936 film Le Roman d'un Tricheur, narrated throughout by the protagonist, calling it "le plus aimable essai de ce genre, au cinématographe".

The opinions stated here are important in understanding Nino Frank's response in 1946 to the Hollywood "films noirs", especially Farewell my Lovely [Murder my Sweet], Laura and above all, Double Indemnity. When he discussed their use of a narrator to delve into the motivations of their characters, thus heightening the sense that they were about real people, with real needs and vices, he was reviving a topic about which he felt strongly, and which had already been exercising him for several years.

Fired again! and a new career

But for some months, Nino had barely concealed his growing disillusionment with his job. He practically ignored the German films released in Paris, or devoted a few desultory sentences to them; and was almost as off-hand about most of the new French films which passed the censor. It is possible that he was becoming alarmed about the ever more pro-German slant of Les Nouveaux Temps: each week a political feature article by Alfred Mallet, disciple and later biographer of Pierre Laval, would chide the French population for their "attentisme" ["waiting to see"] and urge them to fall in whole-heartedly in support of the German project. Even more uncomfortably, Nino had been assigned to ensure that each week any passages found unacceptable by the German or Vichy censors were removed before publication.

On 13th June, 1942, he reviewed La Neige sur les Pas, a French film shot in the unoccupied zone, in a manner which – if not deliberately designed to bring about his dismissal – undoubtedly threw down the gauntlet to his masters. He found the film so tedious and lacking in interest that he devoted almost his entire article to a discussion of the possible meanings of the word 'pas', at the end summing up by saying that the leading actors, Pierre Blanchar and Michèle Alfa, "ont tenu leurs rôles avec un talent consciencieux et estimable. Ils sauvent ce film, dont on n'a rien d'autre à dire." But it is more likely that his first paragraph was what really landed him in trouble, mocking as it did the competence of the Vichy censors:

It retraces on the screen the episodes of a novel by Henry Bordeaux, of the Académie française; and it is yet another story of adultery (this time the cuckold forgives), for 'right-thinking' [bien pensants] and academic novelists are just as susceptible as any other writers to the charm of stories of extramarital affairs. But they do have the advantage of recounting them in such a way that the Vichy censorship is completely fooled. 30 | orig

In any event, in an uncanny echo of his fall from grace in Mussolini's Italy and removal from the journal "900", not only was he immediately relieved of his position, but he was forbidden by the Germans to publish in any papers "de France et de Navarre", i.e. anywhere in France. He later claimed that this was because he did not remove a comment which they had censored (possibly the one just quoted), saying in a radio interview in 1964: "J'ai une histoire assez fâcheuse avec les dictatures, j'ai exprimé je ne sais quel jugement qui leur avait déplu".

But he was probably not too upset, as for some months his interest and ambition had been elsewhere. Marcel L'Herbier offered him the opportunity to try his hand at scriptwriting, and later, in a comment in his Petit Cinéma sentimental, he admitted that he had in fact been trying to get out of journalism:

I wouldn't swear that my enthusiasm wasn't something to do with my desire to make a definite break with journalism. 31 | orig

Entr'acte

The second half of Nino Frank's book Petit Cinéma sentimental is devoted almost entirely to his short career as a scriptwriter (1942-1947), and is the best source of information about this part of his career. But here, as a short introduction, we describe how he entered into this craft, what it taught him about the cinema, and how he realised that he was not really suited to it. (However, it did serve as a valuable apprenticeship for the much freer world of radio writing and production, in which he subsequently worked for two decades.) We also cover his criticisms of the rigid conventions of the cinema of the time, against which he – along with new writers like Alexandre Astruc – would battle when he re-entered cinema journalism in 1945, at L'Écran français.

We know from letters he received from Marcel L'Herbier, held at the Bibliothèque Nationale, that since the late 1930s L'Herbier had been asking Nino to publish, in Pour Vous or L'Intransigeant, articles he had written on the cinema. He had also been pumping him for ideas for new films, and in 1941, thus a year before the critic left his journalistic work, he gave him opportunities to try his hand at scriptwriting. In the next two years Nino worked on an adaptation of Gérard de Nerval ('Sylvie'), which was never made; he edited La Nuit fantastique, scripted by Louis Chavance and Henri Jeanson; he wrote the screenplay for L'Herbier's Vie de Bohème, which to his chagrin was greatly changed after it left his hands; and he was fully responsible for the adaptation from an Italian scenario of the well-received Service de Nuit (released 1944). 32

But it was in his first scriptwriting experience – of trying to turn Gérard de Nerval's fantastical, dreamlike story of 'Sylvie' into a film – that he formulated, from the viewpoint of the practitioner and not simply the critic, his fundamental problem with film story-telling. His description of the accepted practice of the time bears an eerie similarity to much more recent theories about the requirement for a film plot to be built around a precisely-defined 'Quest', pursued in accordance with strict rules:

For the first time...I was meeting on my path "the story" – the circle rigorously closed, the well-turned anecdote, the events whch follow on logically... and "the conflict", the artificial opposition of desires and destinies, through which it is claimed to concentrate the whole of life into 100 minutes of projection. That is, let's put it bluntly, anti-poetry. And there was I believing that in the pages of Gérard would be found enough charm, in the landscapes of the Nonette river enough beauty to fill kilometers of film!...However much I argued, as I still argue today, that one could make films without a "story", without a "conflict", I was told that all the traditions proved the contrary.

Today [1946], La Règle du Jeu, Human Comedy, Les Enfants du paradis, works that are more significant than twenty-five years of films, provide me with an easy riposte. 33 | orig

As a critic, he had always been uncomfortable with the restrictions imposed by film, in comparison with the written word, on imagination and depth of human feeling, and now he was experiencing this at first hand. For years before the war, he had already been arguing that this was because producers were too risk-averse to be more ambitious, as they claimed – without reliable evidence – that the public preferred the fare they were offered. Ultimately, this fundamental clash of beliefs would lead to his departure from the film industry, back to literature and to the freer environment of radio. Upon his departure in 1948, he published a humorous short story in Cinévogue, ‘Un coup de foudre’, about the world of cinema, in which he did not hide his critical response to the absurdities and venalities fundamental to this world.34

CLICK HERE for the full text of this story, in the original French

But as we shall see in Chapter 11, after the war for a brief period he would join like-minded critics, among them new young cinephiles with new attitudes, at the film magazine L’ Écran français, where he would find agreement with, and development from, his ideas. ( In the course of their debates and explorations he would also develop his ideas about the film noir, discussed in Chapter 11.) The 1948 article by Alexandre Astruc, 'Naissance d'une nouvelle avant-garde: la Caméra stylo' gained its fame from the proposition in its second half that the director would become the author/writer of his own films, a proposition which evolved later into the "auteur" theory; but he put forward a very different idea in the first half of the article, about the already changing face of cinema, which was beginning to aspire to the depths of expression already found in other arts. Chronologically the article does not belong in this chapter, but it is quoted because Astruc was among the young men working at L'Écran français, exposed to the ideas which Nino Frank was passionate about disseminating. Clearly by 1948 he saw evidence that young and not-so-young directors (Renoir appears again) were beginning to experiment with bringing to cinema the extra qualities of literature and other arts:

It is not by chance that from Renoir's La Règle du jeu to the films of Orson Welles and [Robert Bresson's] Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, all the signs of a new film future escape most critics, who anyway wouldn't be capable of seeing them. But it is significant that the works which fail to get the critics' blessing are precisely those on which a few of us agree: we see them, if you like, as heralds of the future.

....Cinema is in the process of becoming quite simply a means of expression, as the other arts have been before it, especially painting and the novel...Little by little, it is becoming a language. A language: a form in which and by which an artist can express his own thoughts – however abstract – or translate his obsessions just as in the contemporary essay or novel. That is why I call this new age of cinema that of the 'Caméra stylo' [the camera-pen]. 35 | orig

Although by the time this article was published, Nino had left L'Écran français, he would undoubtedly have read it, and must have felt vindicated, after all the years of crying in the wilderness.

All translations from European texts are my own.

[CLICK HERE to open notes in a new window]

Notes

1 Nino Frank, 'Avertissement', Le Buveur émerveillé (Paris: Bordas, 1948), p.5.

2 Nino Frank, 'Actualités: Prologue à la guerre', Pour Vous, no.565, 13.9.39, p.13.

3 Nino Frank, 'Actualités', Pour Vous, no.573, 8.11.39, p.13.

4 Jean George Auriol, Letters to Nino Frank, 1.10.39, Fonds Nino Frank, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

5 ibid., 19.10.39.

6 ibid., 10.11.39.

7 Nino Frank, 'Funambulesque interview de Corinne Luchaire', Pour Vous, no.508, 10.8.38, p.3.

8 Marcel Carné, 'Cinéma, vieux frère', Aujourd'hui, no.21, 30.9.40, p.1.

9 Nino Frank, 'La Nouvelle Saison', Les Nouveaux Temps, 1.11.40, p.2.

10 Nino Frank, 'Un comédien allemand dans "Le Maître de poste" ', Les Nouveaux Temps, 15.11.40, p.2.

11 Nino Frank, 'Emil Jannings et Werner Krauss dans "La Lutte héroïque" ', Les Nouveaux Temps, 22.11.40, p.2.

12 ibid. Krauss had starred in the early horror film Das Kabinett des Doktor Caligari, and had become a specialist in elderly, often unpleasant characters.

13 Nino Frank, 'Bas-Fonds', Les Nouveaux Temps, 22.2.41, p.2.

14 ibid.

15 ibid.

16 Approximate English translation: 'In its stark truth, this film lays bare the distress of children abandoned, without a guide, without a defence, without tenderness in their life.'

17 Nino Frank, 'Bas-Fonds', Les Nouveaux Temps, 22.2.41, p.2.

18 Nino Frank, ' "La Fille du puisatier" ', Les Nouveaux Temps, 26.4.41, p.2.

19 Henry de Montherlant, 'Va-t-on laisser mourir la France?', Lectures, no.1, 15.6.41, pp.7-9.

20 Henry de Montherlant, 'Notes du temps présent', La Gerbe, 24.7.41, pp.1 and 9.

21 Nino Frank, 'Pour une inquisition', La Gerbe, 7.8.41.

22 Nino Frank, 'Fabrication en série et "cousu main" ', Les Nouveaux Temps, 30.5.42, p.2.

23 Nino Frank, 'Sur l'écran', Vedettes, no.45, 20.9.41, pp.2, 3.

24 ibid.

25 Nino Frank, 'Sur l'écran', Vedettes, no.57, 13.12.41, p.14.

26 ibid.

27 Nino Frank, ' "La Piste du Nord" ', Les Nouveaux Temps, 21.3.42, p.2.

28 Nino Frank, ' "La Duchesse de Langeais" ', Les Nouveaux Temps, 4.4.42, p.2.

29 Nino Frank, ' "Les Inconnus dans la Maison" ', Les Nouveaux Temps, 23.5.42, p.2.

30 Nino Frank, ' "La Neige sur les Pas" ', Les Nouveaux Temps, 13.6.42, p.2.

31 Nino Frank, Petit Cinéma sentimental (Paris: La Nouvelle Édition), p.127.

32 According to Nino, he himself managed to arrange for Henri Jeanson to work on the dialogue, incognito, since at the time Jeanson was banned by the Germans from all cinema activity. See Petit Cinéma sentimental, p.148. (On the IMDB.com site, Nino is listed as responsible for both adaptation and dialogue.)

33 Petit Cinéma sentimental, p.116.

34 Nino Frank, ‘Un coup de foudre’, Cinévogue, 30.4.48, pp.12,13.

35 Alexandre Astruc, 'Naissance d'une nouvelle avant-garde: La caméra stylo', L'Écran français, no.144, 30.3.48, p.5.

Original quotations from which translations taken

(numbers match relevant endnotes)

1 Nous n'oublierons jamais ce périple bourguignon, nos derniers beaux jours, ces heures de soleil sur une terre gonflée de richesse, ces nuits remplies d'étoiles et de senteurs, tant de beauté à la veille de tant de malheur...

2 Les faits même parlent pour prouver, sans contestation possible, l'indignité inouïe du peintre en bâtiment illuminé...d'un côté le tragique pantin à croix gammée et ses automates de séides, et de l'autre des peuples troublés, émus, se rendant tout à fait compte de l'importance de l'événement, mais résolus et unis, et aux visages déjà illuminés, par le grand sourire serein du courage et du sentiment de la justice. Pas la moindre forfanterie: simplement le droit qui connaît sa force et saura triompher.

3 Des soldats d'infanterie descendent des premières lignes et croisent un convoi d'artillerie qui y monte ... si les artilleurs, près de leurs pièces, ont les visages graves et un peu tendus des hommes qui se dirigent vers la ligne de feu, les fantassins qui en reviennent, et qui ont vécu des journées de bataille, n'en paraissent pas autrement émus. Leurs sourires ont une qualité émouvante: ces hommes sont rodés, et le rodage ne les a pas troublés. Les ressources de vitalité de la France ne seront pas atteintes de sitôt.

4 Mon cher Nino, combien je me réjouis! Combien je te félicite d'être sur la dunette de notre vieux rafiot. Tu devines et tu sais bien que je serai le dernier à te traiter de profiteur et de lâche ventre...Au moins j'espère que tu jouis d'une suffisante liberté de manœuvre et de mouvement. En revanche, évidemment, la matière est, si l'on peut dire, moins riche qu'en temps normal...

5 Mon cher Nino, je dois t'avouer, étant donné l'amitié que j'ai pour toi que ton geste inconsidéré (ou désespéré, ou dandygue, ou provocant?) m'a ahuri. Où va se nicher la pudeur? ou le romantisme feuilletonnesque des films américains a-t-il fait de toi un grand enfant? Enfin as-tu oublié quelle application, quelle énergie tu as dû mettre pour vaincre une maladie redoutable et qui ne demande qu'à repasser à l'offensive?

6 Ta place est chez Havas...!

Pour ce qui est de la "vie au grand air" qui te grise les cellules cylindraxiles, je te recommande les casements de la ligne, la glaise lorraine, le brouillard du Rhin ou de la Moselle, la neige déjà apparue, et l'atmosphère confinée des états-majors. Je t'en conjure, reviens au cinéma et aux spéculations gratuites. Tu me reconnaîtras cette honnêteté, et cette pudeur.

7 Dernière image de la tragi-comédie: assis sur le pare-choc d'une somptueuse voiture (la vôtre? la mienne? Je ne me souviens plus de ce que nous avions décidé que je dirais), vous deviez simuler le baîllement profond de l'interviewée lassée par la "question": vous aviez mis si peu de vérité dans votre baîllement que je vous en remercie encore...

8 Certes il va falloir t'adapter, abandonner le visage douloureux et crispé d'hier, celui atrocement ridé d'aujourd'hui. A une période de réconstruction doit correspondre le visage positif de l'espoir. Celui de la jeunesse et de la féerie également...

quelque chose de l'émotion contenue d'un Feyder, de l'étincelle passionnée d'un Renoir, de la tendre ironie d'un René Clair, ou de la puissance d'un Duvivier.

9 Cinématographiquement parlant, nous étions condamnés à n'être plus qu'une colonie d'Hollywood, comme si, brusquement, nous avions cessé de faire partie de l'Europe, d'être solidaires de ce continent qui est le nôtre....encore sevrés de films français récents ou nouveaux, nous venons enfin de prendre contact avec quelques-unes des bonnes productions allemandes de ces dernières années.

10 deux films allemands des plus remarquables, Le Maître de poste, de Gustav Ucicky, et La Lutte héroïque, de Hans Steinhoff, où l'on peut applaudir justement Heinrich George, et, d'autre part, Emil Jannings et Werner Krauss....Et, bien que les deux ouvrages méritent des éloges pour leur style et leur composition, l'intérêt qu'on y prend naît en premier lieu de l'interprétation que donnent de leurs rôles ces fameux comédiens.

11 Les trois grands acteurs allemands: Heinrich George, ou la truculente sincérité faite homme; Emil Jannings, ou la machine à faire vrai, mais rien que vrai; Werner Krauss, enfin, ou le maître de l'indéfinissable, du complexe, de l'énigmatique...

12 il y a de tout dans son aspect – du gâtisme, de la sournoiserie, l'inertie profonde de l'homme arrivé et trop âgé, de la férocité, une étonnante dignité, et jusqu'à cet extrême amenuisement physique et moral, qui est le fait de certaines vieillesses trop recroquevillées dans leur gloire. Il paraît impossible de mettre plus de sens dans un rôle et d'aller aussi loin dans l'interprétation, par l'intérieur.

13 Là-dessus, Veit Harlan a greffé de curieux et truculents épisodes.

14 à lui seul, il est tout un ghetto. L'étourdissant comédien!

15 son interprétation du rôle du rabbin Loew, où on sent mieux que l'adresse, plus même que de l'art - la véritable création d'un être terriblement vivant dont il est impossible de perdre le souvenir... celui du rabbin Loew, ruisselant de vieillesse et de criarde sagesse, familier des astres et des accommodements avec Jéhovah, bourru, chancelant, tout en tics, mi-végétal, mi-fantôme.

17 L'Enfer des Anges nous présente une histoire d'enfants abandonnés qu'interprètent d'étonnants petits comédiens, aussi pittoresques, aussi vifs que ceux de la fameuse Rue sans issue et des autres films américains de la même veine: rien de plus sympathique.

La mort et la solitude devraient être le terme de leur histoire: par la volonté des marchands de pellicule, ce sera la guérison miraculeuse, les fleurs sur le lit à l'hôpital, des hourras, et sans doute la perspective d'un mariage avec beaucoup d'enfants... N'insistons pas.

18 Est-ce du cinéma? Qui se souvient encore de la querelle que certains, voilà quelques années, cherchèrent à Marcel Pagnol? Cet auteur, quittant le théâtre, avait déclaré qu'il se consacrerait désormais au cinématographe; et, en tant qu'auteur dramatique, il affirma l'importance élémentale du texte, allant jusqu'à afficher un certain dédain a l'égard de l'apport particulier des images mouvantes. On l'attaqua, on discuta, on le blâma. Et Marcel Pagnol, entre temps, faisait César, Angèle, hier La Femme du boulanger, aujourd'hui La Fille du puisatier. Dans tous ses films, pourtant, le texte constituait, ainsi que l'avait toujours prétendu Marcel Pagnol, la base de l'œuvre: mais l'auteur s'attachait à animer et à varier les images, comme le plus orthodoxe des metteurs en scène. Et cela faisait d'excellent cinéma, – car cent discussions d'ordre théorique ne valent pas un bon film, et un homme comme Marcel Pagnol ne pouvait pas ne pas réussir de bons films...

La Fille du puisatier n'est probablement pas un chef-d'œuvre. Mais c'est, tout simplement, une œuvre; et le cinématographe n'en produit guère, dans le monde entier, qui prolongent en nous leur signification, qui nous présentent quelque chose de plus que d'agréables images, qui ennoblissent, pour tout dire, par leur profonde sincérité, l'industrie des caméras et des sunlights....Marcel Pagnol et ses interprètes, on ne saurait les comparer qu'à une force de la nature: le génie de l'auteur atteint cette perfection presque tolstoienne, qui fait qu'il écrit et compose, pour ainsi dire, de plain-pied avec l'humain à l'état pur et intégral.

19 Un organisme protecteur de la qualité humaine française, avec un génie d'intransigeance et de coercition. Une sorte d'inquisition au nom de la qualité humaine française.

20 Faire tout ce qu'il faut pour anéantir l'adversaire. Mais, une fois qu'il a montré que c'était lui qui tenait le bon bout, s'allier du même cœur avec lui.

21 Il y a, par ailleurs, la formation des cadres à surveiller, la création d'un centre d'études, comme celui de Cinecittà, la protection des salles de répertoire et des cinémathèques...Demandera-t-on tout cela à des amiraux et à des bureaucrates?

22 Nous tenons en L.-É. Galey, commissaire du gouvernement au Cinéma, un ami passionné de l'art des images mouvantes, qui a déjà donné des preuves de ses bonnes intentions, qui commence à exercer une action sérieuse en faveur du cinématographe de qualité et dont on peut attendre encore des efforts décisifs pour que le film français soit sauvé.

"La production de 1941-1942 a été mauvaise. Celle de 1942-1943 sera moins mauvaise. Elle pourrait être bonne si les producteurs mettaient à leur travail plus de conscience et s'entouraient de plus de talents....Combien de producteurs en sont encore à considérer le cinéma comme une manière d'épicerie, qu'on fabrique à la hâte et qu'on débite a la petite semaine...Je ne veux plus qu'il en soit ainsi désormais. J'ai trop confiance en mon pays pour ne pas être sûr que je serai entendu de tous."

23 Décidément, Henri-Georges Clouzot s'impose comme l'un de nos meilleurs scénaristes et comme l'un de nos meilleurs dialoguistes: son talent est souple et riche, son adresse inépuisable...Après être demeuré longtemps absent des studios, il nous revient avec de nouveaux et bons témoignages de savoir-faire...Applaudissons Henri-Georges Clouzot.

24 Georges Lacombe a su lui donner un rythme rapide et entraînant, qui tient le spectateur en haleine et qui respecte scrupuleusement la loi du genre.

...Pierre Fresnay en tête, qui, dans un de ces rôles traditionnels de policier flegmatique et gouailleur enchante le spectateur par la richesse de son jeu intérieur, l'humeur de ses attitudes et de son parler.

....Suzy Delair, qui, personnifiant une jeune pimbêche, aux reparties rosses, personnage sans doute un peu facile, impose sa ravissante et cocasse autorité.

...un ménage français de policiers de cinéma, dans le genre des fameux Myrna Loy et William Powell.

...L'on plaint le brave commissaire Wens de ne pas découvrir l'assassin dès le début, ainsi que peut le faire toute personne qui a un peu l'habitude de cette sorte d'ouvrages et des trucs faciles qu'utilisent les auteurs dépourvus d'imagination.

25 cette bonne surprise: un large, un pathétique ouvrage, un film magnifique ...rendons grâce à ceux qui ont pris l'initiative de faire achever sommairement ce film et nous le donner aujourd'hui, dans sa robuste et émouvante simplicité, dans sa vérité.

...Rarement, Jean Gabin avait trouvé un rôle qui, autant que le sien dans Remorques, mit aussi nettement en valeur ses meilleures aptitudes...C'est à voir.

...l'âme perdue qui apparaît le temps de reprendre espoir, puis s'en va de nouveau, et son innocent pathétique est l'une des plus grandes lumières de ce film,

...une femme sans bonheur qui se sacrifie humblement, jusqu'à la mort sans phrases.

26 Te souviens-tu, Jean, de nos vagabondages de village à village, avec cette pièce? Tu as été le premier qui m'a dit, devant nos chopines de Meursault, que Remorques serait un grand et bel ouvrage. Cela devait se passer le 15 août 1939. Dix jours plus tard, tu troquais tes loques du "Buveur émerveillé" pour ton uniforme.

27 on ne voit pas, actuellement, en Europe, un metteur en scène capable de donner un style aussi original et aussi éblouissant à une œuvre d'envergure....malgré les imperfections que l'on y aperçoit, il semble bien que La piste du Nord doive prendre, dans l'œuvre de Jacques Feyder, une place de choix: si elle n'a pas l'élégance et le fini de La Kermesse héroïque, l'âpreté pathétique de Thérèse Raquin ou le dynamisme du Grand Jeu, elle se caractérise par une telle qualité de style, surtout dans sa première partie, une sobriété si magistrale dans le récit mais surtout un contenu moral d'une si pure noblesse, que nous avions perdu l'habitude de trouver dans les œuvres de l'écran, qu'il ne sera point interdit d'y chercher le message spirituel de l'un des rares artistes du cinématographe.

28 ce film est moins une adaptation de la fameuse nouvelle de Balzac, moins une réalisation de Jacques de Baroncelli, qu'une œuvre nouvelle de Jean Giraudoux, une histoire attachante et excitante, comme on en souhaite quelques-unes au cinématographe....[Giraudoux] un prince de l'esprit et du style - un poète. Il semble que, sans la moindre hésitation, on devrait se féliciter avant tout que l'art des images mouvantes et parlantes ait gagné un pareil adepte.

...Ainsi, le scénariste, empruntant à Balzac les personnages et le thème, s'est-il trouvé avoir à inventer les péripéties de l'histoire. Reprochera-t-on à Giraudoux d'avoir renoncé à pasticher Balzac pour faire du Giraudoux?....le développement de l'histoire devient beaucoup plus cohérent: si l'apostrophe dans le salon de Mme de Sérizy est un peu trop théâtrale - mais si touchante! – l'intervention de Ronquerolles, à la fin, permet de mieux dessiner la péripétie. L'histoire tient, dans le détail, mieux que chez Balzac.

29 On a fait du cinématographe l'art objectif, voire impersonnel, par excellence, bien qu'en son principe il offrit, mieux que le théâtre, des possibilités d'expression directe à la pensée et à la sensibilité d'un auteur. Ceux qui composent pour l'écran s'effacent scrupuleusement devant leurs personnages, comme si ceux-ci pouvaient jouir d'une existence autonome, ainsi que le prétendaient Unamuno et Pirandello....Considérez pourtant le spectateur de cinéma: ce qu'il demande à l'écran, ce n'est pas une représentation impersonnelle de la réalité, mais une sorte de message humain ou poétique.

...l'auteur dramatique, plus mal partagé que son confrère de l'écran, a essayé, de tout temps, de se mêler à ses personnages: le chœur de la tragédie grecque était, initialement, l'expression de la multitude, donc l'annonce de la fatalité, mais il devenait aisément le véhicule de la pensée de l'auteur. Chaque fois qu'un poète a œuvré pour le théâtre, il a introduit sa propre voix.

...Ces Inconnus dans la Maison sont loin d'être un chef-d'œuvre: j'ai pourtant vu les spectateurs en suivre les péripéties avec une sorte d'angoisse et applaudir à la fin, avec passion, comme à l'issue d'une incantation.

30 Il retrace à l'écran les épisodes d'un roman de Henry Bordeaux, de l'Académie française; et c'est encore une histoire d'adultère (cette fois-ci le cocu pardonne), car les romanciers bien pensants et académiques sont aussi sensibles que les autres au charme des histoires de couchages extraconjugaux. Ils ont cependant l'avantage de les raconter de telle manière que la censure de Vichy n'y voit que du feu.

31 Je ne jurerais pas que mon envie de quitter définitivement le journalisme ait été étrangère à cet enthousiasme.

33 Pour la première fois...je rencontrais sur mon chemin "l'histoire", – la boucle rigoureusement bouclée, l'anecdote bien charpentée, les faits qui s'enchaînent bien...– et "le conflit", – opposition artificielle entre volontés ou destins, par quoi l'on prétend faire tenir en cent minutes de projection un concentré de la vie. C'est-à-dire, tranchons le mot, l'anti-poésie. Et moi qui me figurais que l'on trouverait dans les pages de Gérard assez de charme, dans les paysages de la Nonette assez de beauté pour impressionner des kilomètres de pellicule! J'avais beau prétendre, comme je le prétends encore, que l'on pourrait faire des films sans "histoire" et sans "conflit", on m'opposait toutes les traditions, qui prouvent le contraire.

Aujourd'hui, La règle du jeu, Human comedy, Les enfants du paradis, œuvres plus significatives que vingt-cinq ans de films, me fournissent une réponse facile.

34 Ce n'est pas un hasard si de La Règle du jeu de Renoir aux films d'Orson Welles en passant par Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, tout ce qui dessine les lignes d'un avenir nouveau échappe à une critique à qui, de toute façon, elle ne pouvait pas ne pas échapper. Mais il est significatif que les œuvres qui échappent aux bénissements de la critique soient celles sur lesquelles nous sommes quelques-uns à être d'accord. Nous leur accordons, si vous voulez, un caractère annonciateur.

...Le cinéma est en train tout simplement de devenir un moyen d'expression, ce qu'ont été tous les autres arts avant lui, ce qu'ont été en particulier la peinture et le roman...Il devient peu à peu un langage. Un langage, c'est-à-dire une forme dans laquelle et par laquelle un artiste peut exprimer sa pensée, aussi abstraite soit-elle, ou traduire ses obsessions exactement comme il en est aujourd'hui de l'essai ou du roman. C'est pourquoi j'appelle ce nouvel âge du cinéma celui de la Caméra stylo.