Chapter 9: Nino Frank and 'poetic' realism in French cinema, 1936-1939

"La jeune école française"

When Nino Frank returned fully to film criticism in September 1936, he was struck by the new energy in the Paris cinema scene after a somnolent summer of mediocre 'B' films. In his first serious article in L'Intransigeant, he drew his readers' attention to the fact that "all at once, in this third week of September we are offered eleven films, not one of which seems likely to be of indifferent quality".

Of these eleven films, four were American, one English, one Austrian – and miraculously, considering the difficulties of restricting the number of Hollywood films on Paris screens – French films topped the list with five. For readers' benefit, he listed these: a musical, Le grand Refrain, from Yves Mirande; comedies, sardonic or uproarious, from old favourites like Sacha Guitry, with Le Roman d'un tricheur, and Fernandel, with Un de la Légion; and two films particularly worthy of mention, La belle Équipe from Julien Duvivier, and Jenny from Marcel Carné, "in his début film Jenny (which has been highly praised), a poignant drama with Françoise Rosay and Charles Vanel". He listed briefly the foreign films, ending with the exhortation to his colleagues and his readers: "Right, to work. It's going to be a strenuous autumn."1 | orig

In fact, his colleagues had already noticed something new and worthwhile in the new films from Duvivier and Carné, and were rolling up their sleeves to debate them. In Pour Vous, in adjacent reviews on 17th September, they postulated a new element in these films – a more serious and concerned view of life, which they began to describe as a new 'realism'.

Julien Duvivier was a respected director, known already for many films about the working class, though often in exotic settings – North Africa for La Bandera, Canada for Maria Chapdelaine. But here was a film with a story much closer to home, about a close-knit group of unemployed men, their friendship destroyed by an unexpected lottery win. Jean Vidal, in his Pour Vous critique of La belle Équipe, paid tribute to Duvivier's long experience and technical expertise, while drawing attention to his socially important subject-matter, akin to King Vidor's Our Daily Bread:

With La belle Équipe, M. Julien Duvivier takes on "populist" cinéma...The characters of La belle Équipe are, in fact, unemployed workmen, and their adventure, imagined by Charles Spaak and Julien Duvivier, is not unrelated to that of the out-of-work Americans of King Vidor's Our Daily Bread... The five men are dragging out their miserable lives together, when one evening fortune smiles on them. They win a hundred thousand francs in the lottery. How should they use this money?

And Vidal went on to say:

M. Julien Duvivier has deployed all the skills of his art and his technical experience in a mise en scène which is lively, animated, sometimes hectic.2 | orig

The following week Georges Sadoul, writing in Regards, gave the film even higher praise:

La belle Équipe is a brilliant opening to the French film season. This realist film, an excellent and exact image of life and the problems of men…deserves to be applauded without reserve.3 | orig

Marcel Carné as a director deserved rather different attention. Critics knew him as one of them; until 1932 he had been writing articles in Cinémagazine demanding greater attention in films to real life, and notably to ordinary people. In the intervening years, as Feyder's assistant he had watched the master addressing social questions in his films, albeit often hidden behind historical or other disguises. Feyder had intended to direct Jenny himself, but when for various reasons he could not do so, Françoise Rosay persuaded him to entrust the task to Carné. Thus the subject of the film was not of Carné's choosing, but to critics it was evident that he had put his own stamp on it. The subject-matter tended, to say the least, towards the melodramatic: the owner of a Parisian nightclub of ill-repute, after various misadventures, finds herself ousted from her lover's affections by her own daughter. But Carné's mastery of his medium greatly impressed discerning critics. Thus, Lucien Wahl:

He gives us a masterly work here, a collective work certainly...but collective in the good sense of the word, enabling the coordinator to assert his personality and his love for the cinema. The first images of this integrated yet varied film fill us with a strong sense of reality, then, through all the different scenes and situations, an all-pervading impression of accuracy surrounds us…Jenny will count in the list of important French films. It is varied, true, sincere, strong, as I have said. It does not have a moment of weakness.4 | orig

Even greater praise was given by Alexandre Arnoux, now writing in Les Nouvelles littéraires:

The key event of the season's opening, at least from the French point-of-view, is certainly Jenny, a film which opens up a young director to us. Carné, remember this name...In this first work from his hand we can feel a sensibility, an assurance, an understanding of the cinema, an interior strength which show great promise. Either I'm sadly mistaken or we have here someone of the highest calibre, who I hope will be provided with money and freedom. For the rest, I judge he has the stature to take care of it himself.5 | orig

Although a discordant note could already be heard, it was politically rather than artistically driven: by Lucien Rebatet (writing as François Vinneuil), the extreme rightwing critic who would do his best to destroy Carné's reputation during the coming war. He too appreciated the director's skill, but he hated his subject-matter and was indifferent to the fact that comparison with great German directors like Fritz Lang would be seen as high praise by many critics:

This new young director truly seems born to compose cinema images, something which has been a rare gift in our country until now...[but] you cannot help making a comparison between the airless naturalism of Jenny, this heavy fatalism, and so many Jewish-German films belonging to the socialist period of Berlin and Vienna, which were equally suffocating and despairing...the sadness penetrating everything, daily life and the productions of the mind, in periods of oppression and of marxist chaos like the one we are undergoing now.6 | orig

Thus critics were convinced of a new spirit and a new intention among their directors, which many believed would give French films a new stature on the international scene.

The Hollywood film Fury

But the arrival from America shortly afterwards of Fritz Lang's first Hollywood film, Fury, stung writers into making a more critical appraisal of their own French cinema. The story was a terrifying one: a young man was wrongly accused of kidnapping a child, and was attacked by a lynch-mob. When the sheriff put him in prison, the mob set fire to it. The hero escaped death, disappeared and set out to get his revenge on the mob by engineering their trial for his murder. The film was directed in the expressionistic style for which Lang was known, highlighting the horrors of mob rage.

On 20th October, Roger Régent reviewed the film in L'Intransigeant, praising its frankness about the failings of the American people:

A film like Fury sets up an implacable criticism of this nation of people who find their absolution even in their frankness, in this scrupulous honesty which drives them to parade their sins to try to wash them away. The subject of Fury is the stupidity and cruelty of the crowd when it reacts, collectively, as a mob.

He bemoaned the fact that:

it is absolutely impossible to make films like this in France. Censorship driven by fear and perhaps also a less impartial public, prevents us from revealing ourselves with such frankness...The Americans have the courage to judge themselves: we should regret that we are not equally "sporting".7 | orig

Two days later, Jean George Auriol reviewed the film in Pour Vous, with equal enthusiasm:

What this film is about is the violent, impetuous surge of an angry crowd: the fury of the wild beasts human beings turn into when the instinct of self-preservation arouses hatred and vengeance within them.

He placed particular emphasis on Fritz Lang's European sensibility and the serious films he had chosen to make in Germany:

Fritz Lang, whose important films we have not forgotten – especially the striking M – has succeeded in describing the terrifying hysteria of the mob as never before on the screen: not by magnifying the number of actors, but by throwing light on certain aspects of this mass suddenly without a soul...The cinema has rarely been so eloquent, so alive, so liberated from the novel and at the same time from ideological sermons. I believe that Fury achieves its aim, which is to show the ignominy of lynching, still current today in the United States.8 | orig

These two interventions provided Nino Frank with a springboard for an article – 'Quand on osera se juger' – in which he could re-affirm Régent's objections to French censorship:

With good reason, France is seen today as one of the most liberal countries in the world: we don't suffer from anglo-saxon hypocrisy or scandinavian puritanism. But we have invented something else: our prestige, which we must avoid damaging abroad,

while at the same time returning to his long-term theme, the demand that French filmmakers adopt a more hard-hitting approach taking greater account of reality, like American films of this kind:

What is real, or inspired directly by the real, is dramatically much more convincing than something which is merely imaginary, thus gratuitous...I would simply like French cinema to become more important and indispensable than it is now; to raise its stature by daring to describe what serious books dare to describe; and to admit once and for all that it is possible to make, out of a film, a work of human and international value.9 | orig

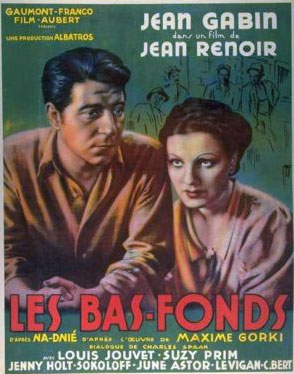

Les Bas-Fonds

With the arrival in November 1936 of Jean Renoir's film Les Bas-Fonds, an adaptation of Gorki's The Lower Depths – about a group of men from different backgrounds who have fallen so low that their only home is a filthy vagrants' hostel – the wish to see French cinema tackle serious social problems began to be realised.

At Cinémonde, the critic Robert Curel felt profoundly the pathos of these characters:

Men with no past, no present, no future, who suddenly betray their anguished torment through their eyes, through their gestures.10 | orig

This film, coming rapidly on top of Jenny and La Belle Équipe, led Georges Sadoul to postulate a new 'realistic' school, naming a number of – mainly experienced – directors as an important "young" French school:

Realism implies knowledge of the world in which we live, a statement that this world contradicts the highest aspirations of man and of the engaged artist, a revolt against the society which has created this inhuman world…The works of Renoir, Carné, Feyder, Duvivier could not have been produced anywhere except in our country…the directors of the young French school, through their remarkable realism, create atmospheres, types, works which will be known throughout the world and which, we can be sure, will have the most profound influence on the evolution of international cinema.11 | orig

The importance of Feyder as the forerunner and inspiration of this "school", and his exploration in his films of the bleaker truths of human existence, was not lost on critics at the time. The link to serious literature - evident in Renoir's Bas-Fonds – and to its dark and often tragic subjects was spelt out explicitly later in Nino Frank's obituary of Feyder:

a black[noire], pitiless representation of existence, a representation which contains nothing of the romantic, which continues in the vein of the great moralists of the eighteenth century – Saint-Simon, Retz, La Rochefoucauld – from whom it takes on the screen, in typically cinematographic forms, its vehemence, intensity and vigour. It is the route of Vigo, Carné, Clouzot, Grémillon, even Duvivier – and it is a route undeniably initiated by Jacques Feyder.12 | orig

Frank’s use of the word ‘noire’ in this paragraph leaves no doubt of its meaning in this context: it is the bleak perception of a world without pity, of an existence with no escape and without external hope, in which the individual is thrown back on himself and often destroyed by his own weakness.

The Prix Louis Delluc

In 1934, the Société d'Encouragement à l'Art et à l'Industrie (SEAI), under the presidency of Louis Lumière, had proudly set up a Grand Prix du Cinéma, with a cash prize for the winner of the award. The first awards went to Duvivier's film Maria Chapdelaine and Feyder's La Kermesse héroïque, and the prize found broad approval in the cinema world. But when in 1936 the rules were changed to allow entry only to films in which not only the director but all those involved were French, important films were disqualified and the quality of the entries went down.

This was the signal for a group of younger critics, led by Maurice Bessy – many of them writers at Pour Vous or Cinémonde – to set up their own award to compete with the Grand Prix, to honour directors working "in the French spirit" even if not all of their collaborators were French. In memory of their great predecessor, they named this the Prix Louis Delluc. For the first award, at the end of 1936, nominations were for two of Renoir's films – Les Bas-Fonds, and Le Crime de Monsieur Lange, from the previous year – and for Jenny, the first film of Marcel Carné, who had rocketed into the esteem of these critics. Renoir won, for Les Bas-Fonds, but voting was very close. To their surprise, the importance of this annual award – and in consequence, the significance of their own opinions – was quickly accepted, not only in France but also in the American movie world. As Frank later wrote:

we discovered that Hollywood film publications were reporting the details of our voting. Zealous correspondents cabled these through, followed up with appropriate, thorough commentaries...When important Hollywood film-makers were in Paris, we invited them to lunch, and praised them fulsomely over dessert...Splendid result, these great men thought we were great men too...13 | orig

Not only did this award become widely accepted in its early years, it has graduated from being an honorary award for talent, with no material prize, to becoming the most prestigious award of French cinema, which has been won by almost all the best-known French directors up to the present day.

It was not only the award which would become very influential, but also the young critics themselves, whose views would shape the critical thought of the future in France and further afield. These critics continued to scrutinise the films of their major directors, and to compare them with their Hollywood competitors, for evidence of the 'realism' which they believed they had perceived.

Pépé le Moko

At the beginning of 1937, Julien Duvivier's Pépé le Moko arrived on Paris screens. This is an interesting film, since its later reputation – especially abroad – has been far greater, amounting almost to cult status, than serious opinion at the time. Duvivier was a director known in France for films which, while sometimes melodramatic or set in exotic locations, attempted to grapple with serious questions. Thus in recent years La Bandera (from Pierre Mac Orlan's novel) had tackled issues of the French Foreign Legion; La belle Équipe, the effects of sudden wealth on social solidarity. The problem for critics was that – brilliantly as it was directed – Pépé did not ring true, and the characters were not sympathetic, or indeed believable.

Frank waxed indignant that the combined talents of Duvivier, Henri Jeanson and Jean Gabin had not produced a more worthwhile film:

the spectator will be held breathless, through a combination of skilful cutting, dialogue with ellipses to be savoured – Henri Jeanson’s best yet – and the excellent acting of Jean Gabin…Why are we not bowled over by all this? Because no-one is bowled over by this kind of plot, a mixture of the artificial and the banal, a collection of inconsistent facts, local colour and conventional characters…in fact, it is no sillier than those of ordinary mass-market films, but Julien Duvivier is worthy of better subjects than these.14 | orig

Maurice Bessy, at Cinémonde, was entranced by Jeanson's dialogue, but felt that it could not make up for the banality of the story and the seediness of the characters:

stunning dialogue, which seduces, convinces, amazes. Dialogue to make even Pagnol or Achard jealous: a living, supple, witty language…[But] Pépé le Moko is a banal story…This gang of professional killers, of hypocrites, of women cut off from their past, is basically repulsive.15 | orig

Pierre Bost at Vendredi was severe, declaring that Duvivier had triumphed in creating a good film from nonsensical subject-matter – but that the falsity of the film and its characters prevented it from being great:

Pépé le Moko is a very good film, but a false great film…it’s a triumph of know-how, of clever crafting…M. Duvivier has succeeded in the feat of making acceptable a subject which had no right to be so, in giving plausibility to all that and, by means of his skill, in making us interested if not in the misfortunes of Pépé and an insufferable high-class tart, at least in the story he tells about them.16 | orig

The main apologist for the film was Marcel Achard, devotee of crime fiction and films, and he applauded it as a straightforward gangster film in the American tradition:

In this genre, the Americans have never done better…Pépé le Moko will probably remain the classic of the gangster saga…Jean Gabin merits a special mention. He’s our James Cagney, our Bancroft and our Paul Muni.17 | orig

A clue to the later ‘cult’ status of this film can be found in Achard’s comment. Through Pépé, Gabin’s film personality was transformed from a working-class protagonist to a glamorous, sharp-dressing, gangster hero, a physical presence which would be echoed in the dashing triumphant soldier at the beginning of Jean Grémillon's Gueule d’amour. Gabin’s charm, and Duvivier’s skill in directing and lighting him – often with a halo of light round his head – led spectators, subconsciously, to warm to a fundamentally sordid character and perceive him as the victim of a cruel fate.

Thus reactions to this film illustrated the concerns which would later lead critics to label only certain Hollywood crime films ‘noir’. They were looking for more than a pacy, stylish intrigue, however well done: it must be underpinned by narrative and moral credibility, and true human feeling.

Gueule d'amour

The emergence of films with a genuine working-class hero rather than a comic buffoon à la Fernandel coincided with the entry into power of the Popular Front, and a brief period of official concern to improve the lot of the poor. Jean Gabin was the personification of such a hero, and by now he was almost indispensable to films dealing with social issues, and especially social class differences. Early in 1937 Jean Renoir's film La grande Illusion, an anti-war film, dared to suggest that it was still the case that French and German aristocrats had more in common than the patrician French soldier with his proletarian counterpart. Pierre Fresnay (the Captain) and Jean Gabin (the Lieutenant) both played French officers, but they were poles apart in social terms. The film was a great success everywhere except in Nazi Germany.

Later the same year, Jean Grémillon's Gueule d'amour appeared, with the same stars as Pépé le Moko – Jean Gabin and Mireille Balin. Grémillon was an accomplished director, who had come to prominence with his 1928 film Maldone, already about a hero struggling to come to terms with his social position – but in this case happier when running away from his rich inheritance than when accepting its responsibilities. This new film – requested by Jean Gabin – would address a rather different aspect of social acceptability: the plight of the soldier (Gabin), dashing in his uniform, who loses his glamour and status – especially to women – in civilian clothes and life. The film was adapted from a novel by André Beucler, known for tackling social issues.

The female protagonist – the exceedingly beautiful Mireille Balin – who ultimately rejects Gabin is also in a social trap: from humble origins, she has become a rich courtesan, and is now not fully accepted among either rich or poor. Certainly the story was melodramatic, ending in the murder of Balin, now exposed as the uncaring femme fatale, but it had credible roots in the attempts of young people to better themselves, in a society stacked against them. It was not so far in feeling from some later Hollywood 'films noirs', and has been described as imbued with "un romanesque noir".

Dead End

So far, all these French 'realist' films were using exceptional social situations to represent broader social problems, partly because of the unspoken censorship discussed earlier in this chapter. But in early 1938, Hollywood would send a further challenge, in the form of William Wyler's Dead End. This film was important in itself, because it appeared to tackle head-on exactly the questions of social injustice which were engaging serious French directors and critics. But it also attracted special attention because the French subtitles had been written by Francis Carco. His involvement is an indication of the close direct links, not always spelt out, between French cinema of the 1930s and the Montmartre writers of the early 1900s, and the cross-fertilisation from Hollywood films. Carco was a novelist, poet, cabaret singer, of the impoverished but brilliant prewar group of Montmartre writers. He was a good friend of Pierre Mac Orlan, who in 1936 described him as one of the most famous names of the early 1900s:

One of the best writers of that time, the novelist and poet Francis Carco…Carco, Dorgelès, Pascin, Chas. Laborde, Max Jacob, Erik Satie, Georges Delaw, André Salmon, Guillaume Apollinaire.18 | orig

In the 1930s Carco gained respectability as a member of the Académie Goncourt, but his heart and his interests were still with the poor and the dispossessed; when Dead End arrived he had been working on the screenplay for a film of his book Prisons de Femmes, directed by Roger Richebé with Pierre Mac Orlan (the latter's only experiment in film directing). It was natural for Jean Vidal, who reviewed the Hollywood film for Pour Vous, to interview Carco about it. At the film’s heart was a potential trigger of tragedy: expensive properties were being built for the rich, right across the river from a poor neighbourhood, goading the poor in their misery, and Carco spoke to Vidal of his feeling of empathy for the characters and their situation, and his admiration for the film’s portrayal of them:

The face of misery is the same everywhere. We find the urchins of Dead End in the slums of all great cities – London, Marseilles, Naples, Berlin. They are depicted here without shame, without reserve, with rare courage.19 | orig

Thus Carco saw the problems and the handling of poverty as worldwide issues, making no distinction between the slums of New York and Marseille. He would later see Carné’s Quai des Brumes as a portrayal of a similar scene of desolation.

The scriptwriter Henri Jeanson, himself a product of the Montmartre slums, wrote for once in uncompromisingly serious vein about the film’s message:

Dead End is a vehement, passionate film. Wretchedness is to the left. Wealth is to the right. That’s all…We meet again in Dead End – although it is an original, violent, colourful film – the mixed pleasures brought to us by Street Scene, Scarface and Freudlose Gasse [Pabst]…Truly, a dead end with no escape.20 | orig

Georges Altman, writing in La Lumière, wrote emotionally of the extraordinary power of the physical images of poverty and despair:

Dead End, which brought to life, in the shadow of rich villas and dance clubs, a poor neighbourhood where unhappiness smoulders before exploding in crime, posed the problem of young people left to themselves, to degeneration…we were transfixed by these images of working-class hovels where coughs ring out in the stairwells, grow louder then fade away, where the mother of the bandit, with her pallid face, her exhausted silhouette, broods on her noir sorrows.21 | orig

All these commentaries illustrate the importance of the connection, for French writers and critics as well as for directors, between the socially concerned films made in Hollywood during the 1930s and the serious films being made in France around the same time. They also indicate that at the beginning of 1938 the existence of poverty and slums was seen by liberal thinkers as a universal problem which governments across the world had so far failed to solve. It was in no sense a phenomenon which the French government needed to seek to deny, or to censor in films.

Official attitudes hardened, however, with the deterioration in the international situation. On 18 March, 1938, German troops marched into Austria in Hitler’s infamous ‘Anschluss’. A ruling which had been sent round the French film industry the previous October by Edmond Sée, President of the Commission de contrôle des films [Board of Censors], and largely ignored, began to be taken seriously, as Roger Régent reported:

It will be forbidden to make films which might harm the good reputation of France abroad, public morals, or the institutions of the State.22 | orig

This meant that the portrayal of inadequate, destitute or criminal citizens of France would in future be fraught with danger – and would certainly risk harsh criticism. Narratives which would previously have been applauded as highlighting misfortune or social deprivation became scandalous to some critics, and the use of the adjective ‘noir’ to describe tragic stories was replaced in certain quarters by its use to mean ‘vicious’, ‘sinful’: unworthy to represent France to the world. The director who would be most affected by the shift in attitudes – lauded in 1938, pilloried in 1939 – was Carné.

Quai des Brumes

Carné's Quai des Brumes, the film which would later be seen as the epitome of the 'noir' sensibility – a compliment, from certain critics; harsh criticism from others – received the highest acclaim when it first appeared in the spring of 1938, but subsequently became the victim of the most splenetic attacks.

Knowledge of the way contemporary attitudes changed towards this film and its director, as Europe moved closer to war, is essential to understanding shifts in interpretation of the word ‘noir’, and to later perceptions of Carné’s work as demonstrating a hopelessness and predisposition to defeat in France. It is also important in countering the later erroneous belief that description of a film as ‘noir’ in France had always been derogatory. What is in debate is not that a generalised negative shift did occur in 1938-39, but how the critics who later initiated the debate about American ‘films noirs’ responded to the films of the late 1930s.23

Nino Frank, with his admiration for Mac Orlan and comprehensive knowledge of his work, seized the opportunity to write on Quai des Brumes. As he often did for films he liked, he wrote a ‘scénario romancé’ of the film. He immediately launched into a description of the setting of Panama’s bar, where the main action takes place, which in its style and content could have come directly from Mac Orlan:

a promontory engulfed in fog – where you stumble over empty sardine cans or disgusting bottles, or even a corpse carried there by the last waves of the night-tide or the archangels of murder. Shall I call it the shore of terror and violent death? No, that of disillusionment and slow death-throes, the meeting place of derelicts, the end of the world.24 | orig

Phrases like "les archanges du meurtre", "la mort violente", "longues agonies" are deliberately reminiscent of Mac Orlan’s preoccupations, and point up the fascination with romantic horror which differentiated his work from the involving but analytical naturalism of a Zola.

The review emphasised that the whole story illustrated one of Mac Orlan’s favourite themes – the supreme rôle in a man’s life not of anything so grandly classical as Destiny, but of simple chance. The tragedy of the hero’s death was encompassed in the insignificant, despairing howl of a lonely dog which thought it had found a friend:

This story is not about morality. I dare not even say…that destiny plays a part. Just chance, and yet…There is no inevitability here, with its great black sails, but simply a sub-product of destiny, not a chorus, not a witness, but just the most heartbreaking symbol: nothing but a yapping, a plaintive bark in the fog, the bark of a lost dog that thought it had found "someone".25 | orig

This article is sufficiently evocative, both of the atmosphere of the film and of Mac Orlan's own style of writing, that it is included below as an Appendix, in the original French.

At Pour Vous, Serge Veber also waxed poetic about the film, and of the importance of Jacques Prévert and Jean Gabin to its success:

An excellent script, intelligent, sober mise-en-scène, fitting dialogue, high-class acting, a great success…From Mac Orlan’s fine novel, Prévert has been able to glean the best elements of his film; he has added some episodes of his own vintage, a younger vintage which, maturing in the bottle, will keep improving…Jean Gabin is the Gabin of great films, the Gabin our bright young things are wild about.26 | orig

No suggestion here of an unacceptably defeatist narrative, or of an inherent pessimism in Carné’s work – this would come later, fed by ‘mauvaises langues’ on the extreme right and left of the political spectrum.

At Vendredi, Pierre Bost was also very complimentary, focussing especially on the masterly build-up of atmosphere in the film:

People will say it is easy to create atmosphere with fog; that it’s enough to film a few fuzzy images. Do not believe it. It is not the fog which gives its colour, its denseness, to this film. It is the subject, the narrative tone, the precision of the scenes, and the progressive unfolding of catastrophe.27 | orig

Commenting on the detail of the subject-matter, Bost admitted that he was not normally an admirer of romantic stories with marginal characters (as witness his earlier comments on Pépé le Moko), but confessed that this time he had been involved in the narrative right to the end and touched by its emotional power:

a work with its own tone, something harsh and bitter, with voices speaking directly to us, touching us without the need for eloquence…M. Jean Gabin has never been better. From one film to the next he gains power and variety; he is truth itself, in this character at once withdrawn but goodhearted, unhappy but tender.28 | orig

The establishment newspaper Le Figaro thought the film’s connection with Mac Orlan, author of the 1927 novel Le Quai des Brumes, important enough to ask him to comment on it before the release. What astounded the writer was the way in which, he considered, Carné and his scriptwriter Prévert had retained the essence of his novel while changing its era, its location and the detail of the hero’s predicament. His novel had been a story of the misery of those living in turn-of-the-century Montmartre, and for him Carné’s film faithfully recreated this misery:

...witness to wretchedness, this wretchedness without a gleam of light which hangs round the slums of towns like an impenetrable fog. Gabin knows this wretchedness and the violent images of its silence.29 | orig

He ended his article with a heartfelt expression of gratitude for so faithful a re-creation of the "fantômes" which had always haunted him:

I can only tell you my gratitude, my deep gratitude. It comes from the year 1927 when, needing a subject to write about, I remembered the atmosphere of this chronicle of hunger. There were ghosts there. These ghosts reappear today in a different setting from an old cabaret in Montmartre. But they are the same ghosts.30 | orig

Continuing the theme of the historical context of the film, two weeks later the newspaper asked Francis Carco, only too familiar with bohemian Montmartre, for his opinion. Carco was even more emphatic that the film was in the direct tradition of Mac Orlan’s writing, especially in its themes of blood and death:

From the first bloodletting, we never ceased to be haunted and pursued by the same sinister image. Blood – wretchedness and blood, hideously glued, stuck, congealed in a horrible mixture – are among Mac Orlan’s favourite themes.31 | orig

He spoke of Prévert’s association with Mac Orlan and ability to translate the nuances of his thinking, and of Gabin’s instinctive understanding of his character’s tragic situation:

M. Prévert, who knows Mac Orlan, has drawn from his work all the desired outcomes and resonances, with artistry, power, tact, frankness which many writers might envy, and Jean Gabin, for his part, has not been afraid to confront the monster face-to-face and grapple ferociously with it.32 | orig

Thus both these writers were of the view that the film was made in the tradition of exposing the tragic lot of the poor and the marginalised, in all places, at all times, and that it also succeeded triumphantly as a work of art.

It will be noted that Gabin featured prominently in these articles and reviews. Indeed, in a later memoir about the 1930s, in a chapter entitled, significantly, ‘Au pays des merveilles’, Frank would say that Gabin – under the stars of Mac Orlan and Prévert – epitomised a period in which it was not yet obligatory to believe establishment propaganda:

It is the Jean Gabin of Quai des Brumes and elsewhere, born of contamination of the passive adventure dear to Pierre Mac Orlan by the caustic mind of Jacques Prévert, two famous poets of a mythology addressed to sceptical readers.33 | orig

The film was an immediate success, and Carné’s mastery of his art was undisputed. It was fêted at Venice, but because of objections from Italian Fascists to the degrading character of its narrative, instead of being the outright winner it was awarded a substitute prize, for mise-en-scène. At the end of the year, the Jury of the Prix Louis Delluc gave Quai des Brumes their seal of approval, with the award of the prize – much to Renoir's annoyance, against the competition of his Bête humaine. Jeanson, as he had done for Renoir two years before, praised Carné unstintingly:

This year the Prix Louis Delluc was awarded to Marcel Carné, the young, courageous, admirable director of Jenny, Drôle de Drame, Quai des Brumes and Hôtel du Nord…It is fitting to associate with his triumph the name of Jacques Prévert, the marvellous dialogue-writer of Le Crime de M. Lange and Quai des Brumes, the singular poet of the songs of Agnès Capri and Marianne Oswald.34 | orig

Lehmann, now the editor of Pour Vous, summed up the year 1938, writing in his leading article on 4 January 1939 of the 'succès éclatant' of French cinema, at home and abroad:

The international public shows a keen taste for French films, impeccably directed, excellently interpreted by outstanding actors, and benefiting from the considerable contribution of talented authors…All the films which are built on plausible and solid plots, which demonstrate the grace and power of French thought, exalt noble, generous ideas, exhibit a vivid understanding and study of human beings: all the films which are truly French in their nature and expression.35 | orig

As it turned out, Quai des Brumes was very successful as far away as Japan, and in America won the National Board of Review’s 1939 award as Best Foreign Film.

In his article Lehmann had chosen to ignore a disturbing trend, evident in some quarters as soon as the film came out. In June 1938 Jeanson reported with anger the reactions of rightwing critics:

The English press devotes enthusiastic articles to the six French films currently on release in London, and notably to a film about the margins of society: Marcel Carné’s Quai des Brumes…against which has been exercised with the greatest violence the eloquence of those who in Le Jour, Gringoire or Je suis partout claim to speak in the name of France.36 | orig

This had been going on for some time, but it was a sinister sign of the new political pressure also on the Left, that Sadoul, after his effusive welcome for Carné and his film Jenny, condemned Quai des Brumes, interpreting it as an unworthy counsel of despair.37 Most wounding, though, was an entirely unexpected attack by Renoir. At a prestigious press conference in July, Renoir accused the film of being Fascist propaganda, because:

it shows defective, immoral, dishonest individuals, and when you see types like these you immediately think there is a need for a master, a dictator, a cudgel to bring back some order.38 | orig

Prévert was furious at this accusation by his friend Renoir, and forced a clumsy apology from him. Jeanson, who loathed the Fascists and the Communists almost equally, accused Renoir with bitter sarcasm of keeping company with both:

The false Renoir of the Communist Party…believes, in fact – just like M. Vil Neuil of Action française – that we should stop making these films about the underclass…The false Renoir never forgets that he is above all a political agent of the Communist Party, disguised as a filmmaker. The Communist Party, I don’t know why, considers Marcel Carné and Jacques Prévert dangerous Trotskyists. Therefore Quai des Brumes is a crime of high treason.39 | orig

The politically motivated sniping would not affect the success of Quai des Brumes, either at home or abroad; but it would have a bearing on Carné’s reputation, both at the time and in the perceptions of later critics.

But what was behind this volte face by Renoir, so wounding to Carné and shocking to many of those who knew him? Possibly he thought Carné was monopolising Prévert, or becoming too closely associated with Gabin. But the actor worked with many directors, and at that time was making a film with Renoir every year. It is perhaps more likely that he did not want to be linked too closely to an exposé of the hopeless plight of much of the working-class in 1930s France, here tackled by a team with personal experience of hardship and suffering. In any event, that summer he was preparing his own film about a similar marginal character, La Bête humaine, drawn from a novel by Zola, with Gabin the main protagonist: but he spun a heroic story about it, comparing it with Greek tragedy:

This engine mechanic drags behind him an atmosphere as heavy as that of any member of the Atrides…To be tragic in the classic sense of the word – and that in a workman’s cap, in mechanic’s overalls and talking like an ordinary person – is a great feat on Gabin’s part.40 | orig

Le Jour se lève

In 1938, Carné made a more conventional film with different scriptwriters and different stars, Hôtel du Nord, which achieved reasonable success but no great critical comment. Then in early 1939, Jacques Viot asked him to read a treatment he had written. Carné was bowled over by the fact that the story was the confession of a murderer, building up the record through a series of flashbacks, while he was trapped by police in a cramped garret with no possibility of escape. Very little detail was in place, but Carné could see the potential for a film building to the tragic climax of the murder and the inevitable ending of the siege. The subject was ideal for Gabin, and was the kind of material which attracted Carné and Prévert. But the key challenge which made Carné determined to tackle this film was the technical one. As he explained to Frank the day after Le Jour se lève opened:

When I say that this is the most difficult film I have made, I am referring specifically to the form, the technique and the style…would the public follow me, would they accept these sudden transitions from a tense and violent present to a slower past?…naturally, the atmosphere has similarities with Quai des Brumes. But it contains less poetry, less psychology, and technique plays a more important part.41 | orig

Evidently even he did not realise at the time quite how effective the technique he had adopted would prove in conveying the hero's psychology.

This film would achieve considerable success when it was re-issued after the war, and would be handsomely praised by André Bazin. (By then, the Hollywood films noirs were also using the flashback technique.) But for now, it was released at an inopportune time, as also was Renoir's La Règle du Jeu. By June 1939 the likelihood of war could no longer be ignored, and it was perhaps not surprising that most critics focused more on the subject than on the revolutionary form taken by the action. An exception was Bessy, who concluded that Carné had succeeded triumphantly in his technique:

Carné has shown real courage in adapting such a literary form, calling on reminiscence and memories to recount an unremarkable news item…The technical ruse gives it a spark and sensitivity which, though artificially created, are insistent: there lies the tour de force, there lies the success.42 | orig

Almost universally, critics praised Carné’s command of his craft; but it was no surprise to find rightwing critics objecting to his subject. The following quotation from Emile Vuillermoz is typical:

a series of magnificent images, treated with intelligence, good taste, and this sombre poetry which is Marcel Carné’s secret. All this is of a wretched dreariness. The author insists on the ugliness, the powerlessness and the flaws of humanity.43 | orig

The most serious and insightful review came from Georges Altman. He stated boldly that the film was a masterpiece, but that the lightweight critics from the daily papers had totally failed to understand it:

Lightweight critics see nothing but a gangster film sequel in one of these rare films we have seen since Pabst and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, which deal with the human condition.44 | orig

The striking aspect of his review, because of the degradation of the word ‘noir’ in much criticism of the period, is its positive emphasis on the word and the concepts implied:

a work which justifies itself, makes its presence felt, through strict cinematic means, with an agonising, noir violence, but utterly pure…at times the film has the subversive power of a dream or a bomb…And for the first time crime, suicide, suffering take on a stark simplicity which awaken no base instincts, which seem to be integrated naturally, fatally, in the blackness of a life without hope.45 | orig

The special quality he saw was that this film was no longer a conventional story of the 'milieu', drawn from an easy literary source, but the tragic story of a man:

Thus the tone is set, in a few bold images with no hint of facile realism or literary populism. We are in the midst of wretchedness and the suffering of men…A man alone and his life count now…images which are never vulgar, banal or morbid. A film which is noir, but fittingly so.46 | orig

Carné would have one final triumph before the outbreak of war. It had been decided that the existing Grand Prix du Cinéma (awarded at the end of each year) did not fully represent the cinema industry; and on 7 July a new official Grand Prix national du cinéma français – instituted by Jean Zay, Minister for Education and the Arts – was awarded, and presented by Zay himself. The prize went to Quai des Brumes.47

With the French declaration of war against Germany, on 3rd September 1939, public admission of any weakness within the State was outlawed, and cinema changed alongside everything else. The next chapter looks at the years of the war and the German Occupation, and in particular at what they meant for Nino Frank.

APPENDIX

Notre scénario romancé, par Nino Frank:

Le Quai des Brumes, film de Marcel Carné et Jacques Prévert

C'est tout au bout de la ville, au bord de l'eau, là où le sol n'appartient à personne, car la mer ni les hommes n'en ont voulu: comme une lèpre entre l'eau grise et la terre habitée - un promontoire imprégné de brumes - où on trébuche dans des boîtes à sardines vides ou d'infâmes bouteilles, quand ce n'est pas dans un cadavre porté jusque là par les dernières ondes de la nuit ou les archanges du meurtre. L'appellera-t-on la plage de la mort violente et de la peur? Non, mais celle de la déception et des longues agonies, le rendez-vous des épaves, le bout du monde et, comme chez Jack London, le "Cabaret de la dernière chance".

Chez Panama, tout de blanc vêtu, en plein vent et en plein brouillard, son couvre-chef acheté en 1906 au bord du canal sur la tête, entre ses bras la guitare qu'il pince assidûment, comme un dément répète sans se lasser le même geste, chez Panama qui ne questionne jamais et bavarde toujours, humant l'air de la nuit avec délices, après avoir éloigné à l'aide de son pistolet les bagarreurs indiscrets, chez Panama qui s'est fait, au Havre, dans son "Cabaret de la dernière chance", le garde-frontière entre les deux pays de la vie et de la mort, et qui essaie de persuader aux passants que la vie, la mort, c'est tout un, il n'y a que les souvenirs qui comptent, et encore...

C'est chez Panama que les personnages de cette histoire échouent, se frôlent, nouent leurs vies puisque le hasard l'a voulu. Panama, lui, il déchiffre peut-être sur leurs fronts les signes que marque la destinée. Mais il n'en dit rien, Panama. À quoi bon? Tout se noie dans la brume, dans cette brume qui remplit la nuit jusqu'au bord. On ne s'écoute que soi-même. On renonce toujours à dire le mot qu'il faudrait, au moment où il le faudrait, car le brouillard vous prend à la gorge. De la veulerie, qu'ils disent, ceux qui n'ont jamais su qu'il existait un fond des choses, et qu'on s'y perd. Ils croient que tout est facile.

Et après? Voilà des gens qui se rencontrent: leurs vies se nouent capricieusement. Mieux encore: ils se soûlent d'espoir - l'espoir de se sauver, l'espoir de s'aimer, l'espoir de vivre. Où cela les mènera-t-il? À ce rire cassé qui résonne à leur oreille au dernier moment, quand le fameux espoir saute comme un bouchon et la bouteille se vide, pourquoi? Parce qu'on a raté le tramway ou parce qu'un petit chenapan s'était persuadé qu'il ne serait un homme que s'il se servait de son pistolet.

*

Un à un, ils avaient fait leur apparition, sortant lentement de la brume, et Panama les avait accueillis sans leur poser de question. Nelly, d'abord. Elle avait quelqu'un à attendre. Qui? Sait-on jamais. Un Maurice quelconque. Ou Jean, le héros sans visage, qui viendrait la sauver. Ou encore Zadel, ce monstre de sournoiserie, le tuteur aux mains sanglantes. Tout, quoi. Ce qui peut venir. La vie, à la place de la mort lente.

Jean, c'est le clochard qui l'avait amené là, le clochard qui rêve d'avoir un lit pour son sommeil, un lit avec de vrais draps propres et blancs. Jean? Un soldat. D'où venait-il? Aucune importance Mais il cherchait à aller loin de l'endroit dont il venait. Et il ne demandait pas mieux que d'échanger son uniforme contre un complet veston même miteux. "On s'en occupera", grommela Panama. Ce fut tout. Qu'importait à Panama, que Jean eût été ramassé par un camionneur à vingt kilomètres de la ville, que leur fraternité eût failli se briser par la faute d'un petit chien perdu que le soldat avait empêché l'autre d'écraser, et que ce chien fut là, maintenant, avec un regard tremblant d'ami, à se frotter aux jambes de Jean, l'affamé? Qu'importait à Panama que Nelly et Jean se soient dévisagés longuement et que, brusquement, on ait senti aux phrases qu'ils échangeaient cette subite unité de ton qui est faite d'ombres et de lumières, et à laquelle on reconnaît que deux vies essaient de s'agripper l'une à l'autre? Panama pinçait sa guitare, derrière son comptoir, et songeait à Panama, le vrai, celui des antipodes.

Krauss, le peintre, Panama le connaissait déjà: un artiste. Il était venu fumer sa pipe en écoutant les autres. Ensuite il alla se jeter dans la mer et disparut à jamais, effectuant ainsi ce suicide qu'il annonçait pour l'heure où il en aurait absolument assez. Son héritage, ce furent son complet veston, son état civil, pour Jean le militaire. "Bonne chance!", dut-il lui souhaiter, avant de se jeter à l'eau, tout en sachant que personne n'a jamais de chance. Restent deux personnages: le hasard les prendra par la perfidie et les ramènera brusquement du second au premier plan. Quand les cœurs s'en mêlent, il faut que la destinée choisisse des instruments sournois, dont on ne se méfie pas. Zadel, tuteur de Nelly, amoureux d'elle, avait tué Maurice, son amant, par jalousie: on l'ignorait encore, et, s'il était venu dans les parages de la guinguette de Panama, c'était justement pour faire disparaître les traces de son crime. Le petit chenapan qui voulait jouer les gangsters, flanqué de deux acolytes aussi veules que lui, prétendait avoir un compte à régler avec Zadel et sa pupille, par amitié pour Maurice. Ces deux fantômes sortis du brouillard, Jean aurait pu en débarrasser sa route d'une chiquenaude, s'ils n'avaient pas été le truchement de ces forces qui aiment à brouiller les cartes et à apposer le rire atroce de la mort aux velléités de la vie.

Le Cabaret de la Dernière Chance? Non, il n'y a jamais de dernière chance, et même l'amour ne compte plus quand on est vraiment à bout de rouleau.

*

Ces histoires-là vont toujours vite, car la mort violente se fait ultra-rapide quand il s'agit d'arriver avant la vie.

Voilà Jean et Nelly qui, à l'aube, quittent la guinguette de Panama. On les retrouve au port, assis au bord de l'eau, et déjà Nelly veut persuader Jean qu'il y a autre chose que de l'ordure au fond de la mer. Car elle, Nelly, elle est encore si jeune que son âme s'ouvre vite à l'espoir. Et c'est là que le hasard - ce fil d'Ariane qui semble vous mener vers la libération et qui, en fait, vous mène à votre perte - place sa bombe: au petit chenapan qui vient insulter Nelly, Jean administre une correction passablement sévère et conseille de ne plus reparaître devant lui.

Peu après, ce sera au tour de Zadel de geindre sous la poigne de Jean. Deux bombes valent mieux qu'une, a dû se dire le hasard, ce hasard qui a mené Jean jusqu'à la boutique où se trouvent Zadel et sa pupille. Il l'avait laissée partir, Nelly. Il la retrouve, à présent, mais affolée, car elle vient de découvrir que son tuteur a tué Maurice, que la jalousie de cet homme n'hésite plus devant le crime, et qu'elle doit fuir. "Jean, sauve moi!"

C'est une vieille histoire, comme aurait dit Henri Heine. Ce soir-là, Jean recevra les nippes et le passeport de Krauss, le peintre. Il trouvera aussi une place à bord d'un cargo, qui part le lendemain pour le Venezuela. Il emmène Nelly à la fête et lui laisse croire qu'elle sera sauvée. Puis, le matin suivant, comme la sirène du cargo hurlait, Jean dit tout à Nelly.

Personne ne sera jamais sauvé, car l'espoir n'est qu'illusion, quand il n'est duperie.

À trois heures et demie, une demi-heure avant le départ du cargo, Jean, qui se trouve à bord, ne peut pas résister à son envie de retourner embrasser Nelly et peut-être de la garder. Il arrive chez Zadel, au moment où le tuteur, exaspéré, s'est jeté sur elle: Jean l'assomme. Nelly le pousse à fuir. Il sort de la boutique. La voiture de la petite gouape vient juste de stopper là, parce que le hasard fait bien les choses. Trois, quatre coups de pistolet. Jean s'affale, mort.

Tout est fini.

*

Cette histoire ne comporte pas de moralité. Je n'oserais pas même dire - quoique j'aie écrit à plusieurs reprises ce mot - que la destinée y joue un rôle. Seul le hasard, et encore...

Il ne s'y trouve pas de fatalité à grands voiles noirs, mais simplement un sous-produit de la fatalité, qui n'est pas un chœur, qui n'est pas un témoin, qui est, à peine, le plus désespérant des symboles: rien qu'un jappement, un aboi plaintif dans la brume, l'aboi d'un chien perdu qui croyait avoir trouvé "quelqu'un", qui a mangé goulûment, qui a manifesté son antipathie aux mauvais hommes et sa sympathie à la jeune femme habitée par l'espoir, qui a failli partir vers la grande aventure, et qui, voilà, disparaît de nouveau dans le brouillard des routes car ses jappements, ses abois plaintifs sont derechef ceux d'un chien perdu.

Pour Vous, le 1 juin, 1938

All translations from European texts are my own.

[CLICK HERE to open notes in a new window]

Notes

1 Nino Frank, 'Du nouveau sur les écrans', L'Intransigeant, 20.9.36, p.8.

2 Jean Vidal, 'Un film "populiste": La belle Équipe', Pour Vous, no.409, 17.9.36, p.6. "Populiste" is a reference to novels like Eugène Dabit's Hôtel du Nord, devoted to the lives of the urban poor.

3 Georges Sadoul, 'La belle Équipe, de Julien Duvivier', Regards, no.141, 24.9.36, p.19.

4 Lucien Wahl, 'Un drame nuancé: Jenny', Pour Vous, no.409, 17.9.36, pp.6-7.

5 Alexandre Arnoux, 'Jenny', Les Nouvelles littéraires, 10.10.36.

6 François Vinneuil [Lucien Rebatet], 'Jenny', L'Action française, 16.10.36, p.5.

7 Roger Régent, 'Furie', L'Intransigeant, 20.10.36, p.7.

8 Jean George Auriol, 'Psychologie de la foule: Furie', Pour Vous, no.414, 22.10.36, p.6.

9 Nino Frank, 'Quand on osera se juger', Pour Vous, no.415, 29.10.36, p.6.

10 Robert Curel, 'Quand la lumière pénètre dans les Bas-Fonds', Cinémonde, no.424, 3.12.36, p.897.

11 Georges Sadoul, 'A propos de quelques films récents', Commune, no.39, November 1936, pp.376-377.

12 Nino Frank, ‘Jacques Feyder, la justesse de l’expression’, in Jacques Feyder ou le cinéma concret (Bruxelles: Comité National Jacques Feyder, 1949), p.26.

13 Nino Frank, Petit Cinéma sentimental (Paris: La Nouvelle Édition, 1950), p.89. The original members of the Jury for this prize were: Marcel Achard, Georges Altman, Claude Aveline, Maurice Bessy, Pierre Bost, Odile Cambier, Suzanne Chantal, Louis Cheronnet, Émile Cerquant, Georges Charensol, Georges Cravenne, Benjamin Fainsilber, Nino Frank, Paul Gilson, Paul Gordeaux, Pierre Humbourg, Marcel Idzkowski, Henri Jeanson, André Le Bret, Roger Lesbats, Pierre Ogouz, Roger Régent and Jean Vidal. Almost all these young people were either already significant voices in the film industry, or would become so in the future.

14 Nino Frank, 'A la casbah d'Alger: Pépé le Moko', Pour Vous, no.429, 4.2.37, p.14.

15 Maurice Bessy, 'Pépé le Moko', Cinémonde, no.423, 4.2.37.

16 Pierre Bost, 'Pépé le Moko', Vendredi, no.67, 12.2.37, p.5.

17 Marcel Achard, 'Pépé le Moko', Marianne, no.225, 10.2.37, p.17.

18 Pierre Mac Orlan, La Chronique filmée du mois, no.32, November 1936, reprinted in ‘La chanson’, Les Cahiers Pierre Mac Orlan, no.11 (Paris: Prima Linea, 1996), p.26.

19 Jean Vidal, ‘Francis Carco nous parle de Rue sans Issue dont il a rédigé les sous-titres’, Pour Vous, no.479, 19.1.38, p.6.

20 Henri Jeanson, ‘Rue sans Issue’, La Flèche de Paris, 22.1.38, collected in Jeanson par Jeanson (Paris: Eds. René Chateau, 2000), p.184.

21 Georges Altman, ‘De Kipling aux gangsters, avec le souvenir de Pearl White’, La Lumière, no.618, 10.3.38, p.5.

22 Roger Régent, ‘Un contrôle? Non, une menace! La censure devient plus tyrannique’, Pour Vous, no.478, 12.1.38, p.5.

23 See comprehensive surveys of critical commentaries by Richard Abel, French Film Theory and Criticism 1907-1939, and Charles O’Brien, ‘Film Noir in France: Before the Liberation’, Iris, no.21, Spring 1996.

24 Nino Frank, ‘Scénario romancé: Le Quai des Brumes’, Pour Vous, no.498, 1.6.38, p.14. The importance of chance features throughout Mac Orlan's work; for a succinct description of the workings of fate, see his short story of 1925, Les trois dés, in the collection Manon La Souricière, Nouvelle Revue Française (Paris: Eds. Gallimard, 1986), pp.9-15.

25 ibid.

26 Serge Veber, ‘Quai des Brumes’, Pour Vous, no.497, 25.5.38, p.4.

27 Pierre Bost, ‘Quai des Brumes’, Vendredi, 27.5.38, p.5.

28 ibid.

29 Pierre Mac Orlan, ‘A propos du Quai des Brumes’, Le Figaro, no.138, 18.5.38, p.4.

30 ibid.

31 Francis Carco, ‘La magie de Carné’, Le Figaro, no.152, 1.6.38, p.4.

32 ibid.

33 Frank, Les années 30, où l’on inventait aujourd’hui (Paris: Pierre Horay, 1969), p.147.

34 Henri Jeanson, ‘Quai des Brumes: Prix Delluc 1939’, La Flèche de Paris, 30.12.38, collected in Jeanson par Jeanson, pp.213-4.

35 René Lehmann, ‘Belle année pour le film français’, Pour Vous, no.529, 4.1.39, p.2.

36 Henri Jeanson, ‘Les films du Milieu ou quand les moralistes s’en mêlent’, La Flèche de Paris, 17.6.38, in Jeanson par Jeanson, pp.199-200.

37 See Georges Sadoul, ‘Quai des Brumes’, Regards, no.228, 26.5.38, p.16.

38 Reported by Marcel Lapierre in Le Merle blanc, no.20, 16.7.38, p.4.

39 Henri Jeanson, ‘Jean Renoir: le plus grand metteur en scène du parti communiste français’, La Flèche de Paris, 12.8.38, collected in Jeanson par Jeanson, p.201.

40 Jean Renoir, 'Trois vedettes dans La Bête humaine', Cinémonde, no.529, 7.12.38, p.1057.

41 Nino Frank, ‘ Le Jour se lève est le film qui m’a coûté le plus d’efforts… nous dit Marcel Carné,’ Pour Vous, no.553, 14.6.39, p.14.

42 Maurice Bessy, ‘Le Jour se lève’, Cinémonde, no.557, 27.6.39, p.2.

43 Emile Vuillermoz, ‘Le Jour se lève’, Le Temps, 17.6.39, p.5.

44 Georges Altman, ‘Le meilleur film du trio Carné-Prévert-Gabin: Le Jour se lève, une œuvre noire et pure’, La Lumière, no.632, 16.6.39, p.5.

45 ibid.

46 ibid.

47 See report in Cinématographie française, no.1079, 8.7.39, p.9.

Original quotations from which translations taken

(numbers match relevant endnotes)

1 d'un seul coup, pour cette troisième semaine de septembre, on nous offre onze films dont pas un ne paraît devoir être indifférent.

...qui débute, avec Jenny (dont on dit le plus grand bien), un drame poignant, avec Françoise Rosay et Charles Vanel.

Allons, au travail. L'automne s'annonce rigoureux.

2 Avec La belle Équipe, M. Julien Duvivier affronte le cinéma "populiste"...Les personnages de La belle Équipe sont, en effet, des ouvriers, des chômeurs, et leur aventure, imaginée par Charles Spaak et Julien Duvivier, n'est pas sans rapport avec celle des chômeurs américains du Pain quotidien de King Vidor...Les cinq hommes traînent ensemble leur vie misérable, quand, un soir, la chance leur sourit. Ils gagnent cent mille francs à la loterie. Comment employer cet argent?

Toutes les ressources de son art et de son expérience technique, M. Julien Duvivier les a déployées dans une mise en scène vivante, mouvementée, trépidante parfois.

3 La belle Équipe inaugure brillamment la saison du cinéma français. Ce film réaliste, image excellente et juste de la vie et des soucis des hommes...mérite d'être applaudi sans réserve.

4 Voici qu'il nous donne un ouvrage de maître, ouvrage collective certes...mais collectif dans le beau sens du mot, et qui permet à l'animateur d'affirmer sa personnalité et son goût pour le cinéma. Ce film, uni et varié à la fois, nous fait entrer dès ses premières images dans une atmosphère de réalité sensible, et ensuite, quels que soient décors ou situations, une impression prenante d'exactitude nous enveloppe...Jenny comptera parmi les films français importants. Il est divers, vrai, sincère, fort, on l'a fait comprendre tout à l'heure. Il n'a pas un instant de faiblesse.

5 L'événement capital de ce début de saison, au moins du point de vue français, c'est certainement Jenny, film qui nous révèle un jeune metteur en scene. Carné, retenez ce nom...On perçoit dans ce premier ouvrage sorti de sa main une sensibilité, une sûreté, une entente du cinéma, une force intérieure qui promettent beaucoup. Ou je me trompe fort ou nous tenons un homme de grande classe à qui je souhaite qu'on fournisse seulement l'argent et la liberté. Pour le reste, je le juge de taille à s'en charger lui-même.

6 Ce débutant paraît vraiment né pour composer des images de cinéma, ce qui est jusqu'à présent, chez nous, un don assez rare...[mais] on ne peut s'empêcher d'établir une comparaison entre ce naturalisme sans air de Jenny, ce fatalisme pesant, et tant de films judéo-germaniques qui appartinrent à la période socialiste de Berlin et de Vienne, qui étaient aussi étouffants et désespérés...la tristesse qui imprègne tout, la vie quotidienne et les productions de l'esprit dans les époques d'oppression et de chienlit marxiste comme celle que nous sommes en train de subir.

7 Un film comme Furie dresse un réquisitoire implacable contre ce peuple qui trouve son absolution dans sa franchise même, dans cette honnêteté scrupuleuse qui le pousse à étaler ses tares pour essayer de les laver. Le sujet de Furie est la bêtise et la cruauté de la foule dans ses réaction collectives.

...il est absolument impossible de faire en France de tels films. Une censure craintive, et peut-être aussi un public moins impartial, interdisent que nous nous montrions avec cette franchise...Les Américains ont le courage de se juger: regrettons de ne pas être aussi "sport".

8 C'est du mouvement violent et impétueux d'une foule irritée qu'il s'agit: de la furie de ces bêtes sauvages que deviennent les humains quand l'instinct de conservation excite en eux la haine et la vengeance.

...Fritz Lang, dont on n'a pas oublié les films importants, le saisissant "M" en particulier, a décrit l'effrayante hystérie de la foule comme jamais on n'y avait réussi à l'écran: non pas en multipliant les figurants, mais en éclairant certains aspects de cette masse soudain privée d'âme...Le cinéma a rarement été aussi éloquent, aussi vivant, aussi libéré du roman et du prêche idéologique en même temps. Je crois que Furie atteint son but, qui est de montrer l'ignominie du lynchage, encore en usage aujourd'hui aux Etats-Unis.

9 La France passe, à bon droit, actuellement, pour l'un des pays les plus libres du monde: nous n'y connaissons pas l'hypocrisie anglo-saxonne ou le puritanisme scandinave. Mais nous avons inventé autre chose: notre prestige, auquel il faut éviter de nuire auprès de l'étranger.

Le vrai, ou ce qui s'inspire directement du vrai, porte, sur le plan dramatique, bien plus loin que ce qui est simplement imaginaire, donc gratuit...Je voudrais simplement que le cinéma francais devienne quelque chose de plus important et nécessaire que ce qu'il est; qu'il s'ennoblisse en osant raconter ce que le livre ose raconter; et qu'il admette une fois pour toutes qu'on peut faire, d'un film, une œuvre de valeur humaine et internationale.

10 Des hommes sans passé, sans présent, sans avenir et qui montrent soudainement l’angoisse tourmentée de leurs regards, de leurs gestes.

11 Le réalisme implique la connaissance du monde qui est le nôtre, la constatation que ce monde contredit les aspirations les plus hautes de l’homme et de l’artiste entraîné, la révolte contre la société qui a créé ce monde inhumain…Les œuvres de Renoir, de Carné, de Feyder, de Duvivier n'auraient pu être produites ailleurs que dans notre pays...la jeune école française, par son réalisme remarquable, crée des atmosphères, des types, des œuvres qui seront connus du monde entier et qui auront, nous en sommes sûrs, l'influence la plus profonde sur l'évolution du cinéma international.

12 une représentation noire et impitoyable de l’existence, représentation qui n’a rien de romantique et qui prend sa place dans la lancée des grands moralistes du XVIIe, les Saint-Simon, les Retz, les Rochefoucauld, de qui elle reprend, à l’écran, dans des formes typiquement cinématographiques, la véhémence, l’intensité et la vigueur. C’est la voie des Vigo, des Carné, des Clouzot, des Grémillon, des Duvivier même – et c’est une voie dont Jacques Feyder a été indéniablement l’initiateur.

13 nous découvrîmes que les publications cinématographiques d'Hollywood donnaient le détail de nos tours de scrutin. Des correspondants zélés les câblaient et on les faisait suivre de commentaires appropriés et copieux...Nous invitâmes à déjeuner, lors de leur passage à Paris, des notabilités d'outre-Atlantique, et leur rendîmes aimablement hommage au dessert...Chose admirable, ces grands hommes nous prenaient nous-mêmes pour de grands hommes...

14 il tiendra le spectateur en haleine par les vertus conjuguées d’un découpage adroit, d’un dialogue aux raccourcis savoureux – le meilleur qu’ait signé Henri Jeanson – et de la très belle interprétation de Jean Gabin… Pourquoi tout cela n’est-il pas bouleversant? Eh bien, parce qu’on ne bouleverse jamais personne avec des scénarios de ce genre, mélange de factice et de banalité, collection de faits sans consistance, de couleur locale et de personnages conventionnels…en fait, il n'est pas plus bête que celui des films de série ordinaires, mais Julien Duvivier mérite mieux que de pareils sujets.

15 un dialogue étourdissant, qui emballe, entraîne, émerveille. Un dialogue à rendre jaloux Pagnol et Achard réunis: une langue vivante, souple, spirituelle…[mais] Pépé le Moko est un drame banal…Cette bande de tueurs professionnels, d’individus hypocrites, de femmes sans souvenirs, est en elle-même assez répugnante.

16 Pépé le Moko est un très bon film, mais un faux grand film…c’est le triomphe du savoir-faire, de la bonne fabrication…M. Duvivier a réussi ce tour de force de rendre acceptable un sujet qui n’avait pas le droit de l’être, de donner de la vraisemblance à tout cela, et, à force d’adresse, de nous intéresser, sinon aux malheurs de Pépé et d’une poule de luxe insupportable, au moins au récit qui nous en est fait.

17 Dans le genre, les américains n’ont pas fait mieux…le classique de l’épopée gangster demeurera probablement Pépé le Moko…Jean Gabin mérite une mention spéciale. C’est notre James Cagney, notre Bancroft et notre Paul Muni.

18 Un des meilleurs écrivains de ce temps, le romancier et le poète Francis Carco… Carco, Dorgelès, Pascin, Chas Laborde, Max Jacob, Erik Satie, Georges Delaw, André Salmon, Guillaume Apollinaire.

19 C’est que la misère a partout le même visage. Les voyous de Rue sans Issue, on les retrouve dans les bas-fonds de toutes les grandes villes, que ce soit à Londres ou à Marseille, à Naples ou Berlin. Ils sont dépeints ici sans pudeur, sans concession, avec un courage peu commun.

20 Rue sans Issue est un film véhément, un film passionné. La misère est à gauche. La richesse est à droite. Voilà tout…On retrouve dans Rue sans Issue – qui demeure pourtant un film original, violent et coloré – les joies mélangées que nous procurèrent Street Scene, Scarface, et La Rue sans Joie [Die Freudlose Gasse de Pabst]…Sans issue en effet.

21 Rue sans Issue, qui faisait vivre, à l’ombre des villas riches et des dancings, un quartier de pauvres où le malheur couve avant d’éclater en crime, posait le problème de la jeunesse livrée à elle-même et à la déchéance… l’on restait saisi à ces images de taudis ouvriers où les toux sonnent, montent, s’étouffent dans les escaliers, où la mère du bandit, avec son visage ex-sangue, sa silhouette épuisée, rumine son noir chagrin.

22 Il sera interdit de faire des films qui pourraient nuire au bon renom de la France à l’étranger, à la morale publique, aux institutions de l’Etat.

24 un promontoire imprégné de brumes – où on trébuche dans des boîtes à sardines vides ou d’infâmes bouteilles, quand ce n’est pas dans un cadavre porté jusque là par les dernières ondes de la nuit ou les archanges du meurtre. L’appellera-t-on la plage de la mort violente et de la peur? Non, mais celle de la déception et des longues agonies, le rendez-vous des épaves, le bout du monde.

25 Cette histoire ne comporte pas de moralité. Je n’oserais pas même dire…que la destinée y joue un rôle. Seul, le hasard, et encore…Il ne s’y trouve pas de fatalité à grandes voiles noires, mais simplement un sous-produit de la fatalité, qui n’est pas un chœur, qui n’est pas un témoin, qui est, à peine, le plus désespérant des symboles: rien qu’un jappement, un aboi plaintif dans la brume, l’aboi d’un chien perdu qui croyait avoir trouvé "quelqu’un".

26 Un excellent scénario, une mise en scène intelligente et sobre, un dialogue juste, une interprétation de très grande classe, un beau succès…Dans le beau roman de Mac Orlan, Prévert a pu glaner les meilleurs éléments de son film; il y a ajouté quelques episodes de son cru, un cru plus jeune qui, en prenant de la bouteille, ira en se bonifiant…Jean Gabin est le Gabin des grands films, le Gabin dont raffolent toutes nos belles-de-jour.

27 On dira que c’est facile de créer une atmosphère avec de la brume; qu’il suffit de faire des images un peu floues. N’en croyez rien. Ce n’est pas la brume qui donne sa couleur, son épaisseur, à ce film. C’est son sujet, le ton du récit, l’exactitude des scènes, et la naissance progressive d’une catastrophe.

28 une œuvre, qui a un ton bien à elle, quelque chose de dur et d’amer, avec des éclats de voix très directs, et qui nous touchent sans recourir à l’éloquence…M. Jean Gabin n’a jamais rien fait de meilleur. De film en film il prend plus de force, et aussi plus de variété; il est la vérité même, dans ce personnage à la fois fermé et bon, malheureux et attendri.

29 …témoignage de la misère, cette misère sans éclat qui traîne dans les bas quartiers des villes comme un brouillard impénétrable. Gabin connait la qualité de cette misère et les images violentes de son silence.

30 Je ne peux vous dire que ma gratitude. Elle est profonde. Elle vient de cette année 1927 où, pour écrire, je me rappelais l’atmosphère de cette chronique de la faim. Il y avait là des fantômes. Ces fantômes réapparaissent aujourd’hui dans un autre décor que celui d’un vieux cabaret de Montmartre. Mais ce sont bien les mêmes.

31 Depuis le premier sang versé, nous n’avons pas cessé d’être hantés et poursuivis par la même et sinistre image. Or, le sang, la misère et le sang, hideusement collés, poissés, agglutinés en un horrible mélange, sont essentiellement des thèmes macorlanesques.

32 M. Prévert, qui connait Mac Orlan, a tiré de son œuvre toutes les conséquences, toutes les résonances voulues avec, d’ailleurs, un art, une force, un tact, une franchise que bien des écrivains peuvent envier et, de son côté, Jean Gabin n’a pas craint d’aborder le monstre face à face et de se colleter farouchement avec lui.

33 C’est le Jean Gabin du Quai des Brumes et d’ailleurs, né de la contamination de l’aventure passive chère à Pierre Mac Orlan par l’esprit corrosif de Jacques Prévert, deux fameux poètes d’une mythologie qui s’adresse aux lecteurs désabusés.

34 On a décerné cette année le Prix Louis Delluc à Marcel Carné, le jeune, le courageux, l’admirable réalisateur de Jenny, de Drôle de Drame, de Quai des Brumes et d’Hôtel du Nord…Il sied d’associer à son triomphe le nom de Jacques Prévert, le merveilleux dialoguiste du Crime de M. Lange et de Quai des Brumes, le singulier poète des chansons d’Agnès Capri et de Marianne Oswald.

35 Le public international montre un goût très vif pour les films français, réalisés d’une façon impeccable, très bien interprétés par des acteurs émérites et bénéficiant de l’apport considérable d’auteurs de talent…Tous les films bâtis sur des scénarios plausibles et bien charpentés, qui montrent la grâce et la force de l’esprit français, tous les films qui exaltent des idées nobles, généreuses, affirment la connaissance et l’étude pittoresque de l’humain: tous les films vraiment français de nature et d’expression.

36 La presse anglaise consacre d’enthousiastes articles aux six films français projetés actuellement à Londres, notamment à un film sur le milieu: Quai des Brumes de Marcel Carné…Quai des Brumes contre quoi s’est exercé avec le plus de violence la verve de ceux qui dans Le Jour, dans Gringoire, dans Je suis Partout prétendent parler au nom de la France.

38 il montre des individus tarés, immoraux, malhonnêtes et que, lorsqu’on voit de tels types, on pense immédiatement qu’il faudrait un maître, un dictateur, une trique pour remettre de l’ordre là-dedans".

39 Le faux Renoir du parti communiste…estime, en effet – tout comme M. Vil Neuil [François Vinneuil] de L’Action française – qu’il faut en finir avec ces films sur la pègre…Le faux Renoir n’oublie jamais qu’il est, avant tout, un agent politique du parti communiste, maquillé en cinéaste. Or, le PC, je ne sais pourquoi, tient Marcel Carné et Jacques Prévert pour de dangereux trotskistes. Donc Quai des Brumes est un crime de haute trahison.

40 Ce mécanicien de locomotive traîne derrière lui une atmosphère aussi lourde que celle de n’importe quel membre de la famille des Atrides…Être tragique au sens classique du mot, et cela en restant coiffé d’une casquette, vêtu d’un bleu de mécanicien et en parlant comme tout le monde, c’est un tour de force que Gabin a accompli.

41 Quand je dis que ce film est le plus difficile que j’aie fait, c’est justement à sa forme, à sa technique et à son style que je fais allusion…le public me suivait-il, accepterait-il ces passages soudains d’un présent extrêmement tendu et violent à un passé plus lent?…l’atmosphère s’apparente, naturellement, au Quai des Brumes. Mais il comporte moins de poésie, moins de psychologie, et la technique y joue un rôle plus important.

42 Carné a fait preuve d’une réelle intrépidité en adaptant une forme très littéraire qui fait appel à l’évocation et aux souvenirs pour nous conter un fait divers assez banal…Le subterfuge technique adopté lui confère un éclat et une sensibilité assez artificielles et pourtant pressantes: là est le tour de force, là est la réussite.

43 une série d’images magnifiques, traitées avec une intelligence, un goût et cette sombre poésie dont Marcel Carné possède le secret. Tout cela est d’une tristesse affreuse. L’auteur insiste sur les laideurs, les impuissances et les tares de l’humanité.

44 Les vaudevillistes ne voient qu’une séquelle des films de gangsters dans un de ces rares films, depuis Pabst et Je suis un évadé [I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang], qui traitent de la condition humaine.

45 une œuvre qui se justifie, qui s’impose, par des moyens stricts de cinéma, avec une violence déchirante, noire, mais d’une parfaite pureté…le film a parfois la puissance subversive d’un rêve ou d’une bombe…Et pour la première fois le crime, le suicide ou la souffrance prennent une simplicité nue qui n’éveillent aucun bas instinct, qui semblent s’intégrer tout naturellement, tout fatalement dans le noir d’une vie sans espoir.

46 Ainsi, en quelques images vigoureuses, qui n’ont rien d’un réalisme facile ni d’un littéraire populisme, l’accent est donné. On est dans la misère et dans la peine des hommes...L’homme seul et sa vie comptent à présent…des images qui ne sont jamais vulgaires, banales, ou malsaines. Un film noir, mais propre.