Chapter 2: Nino Frank and the Italian journal "900"

Paris at last

Now that the chance had arisen, Nino could not wait to get to Paris and settle in, with a job, as a real inhabitant of his adopted city. He had worked very hard, setting up a column in the Nouvelles littéraires to report on Italy, to complement the regular articles he would write in the Corriere della Sera on Paris. He had built up contacts with publishers in Paris, and in Milan and Rome, to promote books by Bontempelli and Mac Orlan, in his own translations; and, together with the Surrealist Philippe Soupault, he was working on an Anthologie de la Nouvelle Prose Française – to feature all the avant-garde writers, naturally including Max Jacob.

He had even stirred up debate in his first news story for the Nouvelles littéraires in February 1926, on a new novel by the Trieste author Italo Svevo, challenging the statement of the esteemed writer Benjamin Crémieux that Svevo had been discovered in France, being "totalement inconnu" in Italy.1 Nino pointed out (from his knowledge of Italian journals) that not only had Eugenio Montale written on his work some months ago in L'Esame, but he also had a very different view of Svevo's talent from that of the Frenchman:

The Esame has gone on the attack, claiming to have discovered Svevo three months ago... While Crémieux denies that Svevo's two earlier books can claim any originality, contrasting them with the third – a novel which caricatures psychoanalysis – the Esame declares that Svevo's value lies in his first two books, reminiscent of Flaubert.2 | original text

Neither party was especially pleased at the intervention, which however undoubtedly brought the young man's name to the attention of the literary world.

Back in Milan in March, he realised that, after the excitement of Paris, he hated the slow provincial tempo of Milan – as he wrote to Bontempelli:

Now that I've become a man of action in Paris, I'm dying of boredom here, surrounded by all these deadbeats. So I work and work. I'm writing two novels and a play, as well as a dozen other things.3 | orig

Finally, in an exceptionally delightful April, he moved into the Hôtel du Bouquet on the Rue de la Harpe in the Latin Quarter, with Nina Ronchi, whom he had persuaded to accompany him for a short while. His job was anything but burdensome, and during the first magical weeks he was entirely wrapped up in this chance to be a lover in Paris. In the kind April weather, and even late into the warm nights, they would wander along the banks of the Seine and in the Luxembourg Gardens, and back to the haunting medieval Musée de Cluny, close to their lodgings. He described this time in his later memoirs:

I was living with an angel...what can be more intoxicating than showing Paris at night to the woman you love? Everything tempted us, in the dim street-lights of the time, but above all the Seine, from the Vert-Galant to the Morgue, still there at the stern of the vessel: but soon invisible ropes hauled us back to the mysterious mass of the ancient stones of Cluny...we were just another couple in love.4 | orig

Paris: L'île de la Cité

However, he had been in Paris for less than a month when he received a letter from Bontempelli, who had had the bold idea of starting a new international literary journal, to be published in Rome and Paris, and to be written in French. The rationale for this seemingly perverse decision was that Italian journals written in Italian reached only a very small readership, while French was the international language for the whole of Europe. Bontempelli's idea was that Nino would run the Paris end of the operation, finding important sponsors and contributors among the avant-garde community there. It is a measure of the undemanding nature of Nino's official job that he replied on 7th May with a four-page letter detailing his ideas for the new journal. How could he have known that this exciting but seemingly innocent choice would set him on a rocky course from which there would be no turning back, and which would change the whole of the rest of his life?

The adventure of the journal "900": early success

Massimo Bontempelli

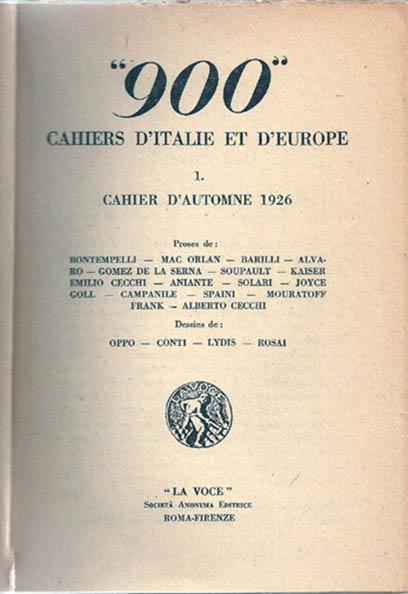

Massimo BontempelliEurope in the 1920s saw a large number of ambitious projects to launch literary magazines. Most of them survived for one or two years at most, failing to build up a reliable regular readership ahead of financial collapse. Bontempelli's project was even more perilous than most, because of its Italian/French duality, and his wish to feature modernist writers from a wide range of nationalities. Against all the odds – including determined opposition in influential quarters in Italy – it survived for five substantial issues in its French form, then continuing for a further two years as an Italian journal. This is the story of its birth and international period, as experienced particularly by Nino Frank in Paris (there are a number of studies by Italian academics on the journal as seen from Rome).

The letter from Massimo sketched in broad terms his conception of the new journal. The name would be "900" ['Novecento': 'Twentieth Century' in Italian], the journal would be written in a spare, modern style – "antilyrical, antisurreal, antipsychological" – and be underwritten by a well-known author in each country represented. For France, he tentatively suggested Louis Aragon.

Louis Aragon was not among the Frenchmen who had befriended Nino, and the young outsider found him rather forbidding. Not only that: he was a key player in the Surrealist group, and closely involved in their journal La Révolution Surréaliste – why should he be interested? Rather than approach him, Nino went straight to a man who was his friend, Pierre Mac Orlan. The choice was a sensible one, since between 1918 and 1925 Mac Orlan had been a literary editor at three separate publishing houses, and was familiar with the personalities, and how matters were arranged, in the French publishing scene.5

Nino's letter of 7th May to Bontempelli shows that Mac Orlan gave him advice on everything he needed to know (after all, he had no idea how to set up a magazine), agreed to be the Paris representative, and proposed his preferred publisher for the French distribution – the one for whom he had worked – Georges Crès:

900 is a marvellous idea and one of your greatest inventions, you were right to think I would be enthusiastic. As you'll have seen in today's Nouvelles littéraires, and as you will see from the cuttings I'll send you from the Gazette du Franc, the Intrans, Paris-Soir, etc., I'm making sure to trumpet the news all over town.

...Aragon isn't right to be our director in Paris, because he is too difficult to work with. It seemed to me that Mac Orlan would be the most suitable choice – first of all for his name, then for his friendships with editors etc., and finally because he is not in the least difficult. I've spoken to him, and he accepts, approves and he too is enthusiastic. Through me he sends you this advice (also he will help me to get manuscripts, he's already suggested it).6 | orig

There followed eight detailed recommendations, on everything from publicity to money, but most importantly on the publishing house to distribute the journal in France. Mac Orlan recommended Crès, and could arrange everything, providing agreement could be reached on the percentage to go to the French distributor – an early warning from Mac Orlan the experienced editor.

It is arguable that without this warm support and practical help from Mac Orlan, the project would never have got off the ground. Bontempelli had no influence in France, and although Nino had been graciously received in many quarters, he was not yet 22, a foreigner with an imperfect grasp of French, and his only experience was in writing for magazines, not running them. The amazing thing about the adventure of "900" is that together these men persuaded some of the most prestigious modernist writers and artists of the age to lend their names and contribute to this journal.

Now began for Nino the most testing six months he had yet experienced. He had to learn all the usual editorial functions – commissioning articles, holding contributors to deadlines, correcting copy, and so on. Not unusually for a new small journal, "900" came low on the list of contributors' priorities, and a great deal of chasing up was required. On top of this, however, as the man on the ground in France it was his task:

- to find international representatives for an editorial board (essentially, well- known names with influence among other writers) for countries outside Italy, through approaches to expatriate communities of writers in Paris

- to arrange paid-for and by-line publicity in as many Paris newspapers and journals as possible

- to negotiate with publishers to obtain a reliable agreement on favourable financial terms, on the Paris end of the arrangement.

All this work – on the top of his paid journalism – was unpaid, but he was carried forward by youthful enthusiasm and the hope of a share in the journal's fame.

The first issue was planned for late September, and editorially, in August things were looking good. Bontempelli and his colleague Corrado Alvaro in Rome had had no difficulty in finding young Italian writers in tune with their ideas and keen to be published. Including short stories of their own, they now had eight Italian contributions – though it would take time for all of these to be translated into French. For the international contributions, in Paris Nino had stories from Pierre Mac Orlan, Philippe Soupault, Georg Kaiser, Ivan Goll and James Joyce; while the Spaniard Ramòn Gomez de la Serna was tracked down in Naples, where he was living, and the Russian Paul Mouratoff was waylaid at the end of a long tour, and persuaded to write about his impressions of Italy.

Four country representatives were also recruited in time for the first issue: Pierre Mac Orlan (France), Georg Kaiser (Germany), James Joyce (Britain) and Ramòn Gomez de la Serna (Spain). The editors were still looking out for writers to represent Russia and America. The journal was publicised in a number of French magazines, notably Les Nouvelles littéraires, and the first issue was anticipated with intrigued curiosity in Paris.

One or two practical hurdles remained. Mac Orlan's short story had not appeared, and he could not be contacted. It turned out that he had started writing Le Quai des brumes, and forgotten everything else; but the story was ready, even if Nino did have to travel out to Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin to collect it himself. More seriously, the French publisher Crès was becoming concerned about the viability of the project and threatening to withdraw. Deadlines had been missed, and the Italian/French contract was still not signed by late September. Reluctantly, Bontempelli capitulated to his demands, although considering them outrageous:

Now Crès has come up with the condition that the dispatch costs (and the return of unsold copies) must be borne by us, which, considering that he is taking 50% (!), even on the copies he has in store, is a scandal.7 | orig

The first issue finally appeared at the end of October.

The list of contributors was impressive, and in both Rome and Paris the editors spoke triumphantly about the journal's warm reception and sales:

In Italy the revue is a great success, it is being talked about and written about everywhere, and is selling magnificently. Alvaro8 | orig

Look, everyone here is talking about "900". And they're asking me how much we've spent on publicity! No revue has ever had such a happy birth. We must make sure to continue the success. Frank9 | orig

In what ways, then, did the new journal diverge from existing – especially Italian – writing? The practical aims behind Bontempelli's idea were: to introduce modern Italian writers (notably himself) to a wider European audience; and to bring to the attention of Italian literary circles, still very insular and backward-looking, modern trends in writing in other western countries. By the mid-twenties, by popular consent Paris was the centre of the European cultural universe, with writers and artists flocking there from across the western world. He reasoned that by publishing his journal in French, in Paris as well as Rome, he would have access to a much wider readership, especially among a public in Paris largely indifferent to Italian letters. (A minor problem would prove to be the disinclination of Italians to read their own authors in French.)

His literary aim, which he found difficulty in summarising, was to encourage Italian writers to experiment more, and cast off their dependence on nineteenth century classicism. In particular, he wanted to see depictions of a world with its own laws, logical yet independent of human agency, in which new relationships of time and space could be imagined, and strange fantasies played out (the basis for what would become known as his own "magic realism"). He wrote a long and rambling introduction to the first issue, to explain his ambitions. The key points for the new writing were:

- "to rebuild and perfect a real world independent of humanity" (p.8)

- "to view life, even at its most ordinary and banal, as a miraculous adventure, a perpetual risk" (p.9)

- "to peel away a corner of the surface of reality to reveal the deeper reality below" (p.174)10 | orig

In the Nouvelle Revue Française, Benjamin Crémieux summed up more concisely, pointing out also the influences which had been important to the Italian:

M. Bontempelli promotes an imaginative realism, the recital or evocation of a world which is imaginary but objectively described, in summary an art quite close to that of Max Jacob, Mac Orlan, Ramòn Gomez de la Serna, and in a certain sense Ariosto.11 | orig

Bontempelli's admiration for Max Jacob was well known, and his search for a world with its own laws, not dictated by man, connects with the cubism of Jacob and his friends.

Thus the brief to his contributors (most of whom sent in short stories) was to allow free rein to their imagination, and not to feel constrained by human convention or logic. A few brief examples show that the best of the stories admirably fulfilled this aim, making the most of surprise or shock endings:

Pierre Mac Orlan, Une Nuit: A story derived partly from genuine memories of his time as a penniless wanderer, driven by hunger into a state of delirium in which strange things happen; the only way he could obtain food was by playing tunes on his accordeon. In this imagined re-creation in a northern port, he played for the filles de joie in a brothel down by the harbour, and towards dawn the wind picked up and turned the building into a sailing boat, taking him and his hungry companions:

towards the island of adventure; a round island with 500 place-settings, covered with a white tablecloth, where wine, coffee and liqueurs were included in the meal which awaited us.12 | orig

Philippe Soupault, Mort de Nick Carter: A spoof on the fictional pulp fiction detective Nick Carter (the American original was much enjoyed by Soupault). The incomprehensible action takes place mainly in a large house which has become a clinic for rich mental patients – a common trope in such stories. A black male nurse has disappeared, a new nurse arrives, and two tramps come over the wall with revolvers. Shots are fired, the patients rush to join in the fight, strangely the black nurse is there, with a bleeding hand, and vanishes again. The new nurse is strangled, the tramps are shot dead. All three are found to be wearing wigs, and it turns out that they are Nick Carter and his faithful assistants. That evening:

A black man with a bandaged hand bought a newspaper, giving the stallholder a 100 franc note. "Keep the change," he said.13 | orig

Pietro Solari, Douze Heures de vie: Two adolescents make love in a wood, at midday. When they try to return home, everything in the town has disappeared or is in ruins: an earthquake has destroyed everything. After wandering for hours, they take shelter under a fallen fig-tree, and cling together for comfort. In this post-Apocalyptic world they hear shooting, as if after a hare, but:

certainly on a night like this no-one would shoot hares. So there must still be living people in this world: people who are shooting each other.14 | orig

Massimo Bontempelli, Femme au soleil ou La promenade bourgeoise: A fantasy of two light aeroplane pilots meeting in the sky and flying together directly towards the sun, in a matter-of-fact way as if they were on an everyday walk together. The narrator discovers that the other pilot is a beautiful woman, and the light around them becomes stronger and stronger until he asks her name: it is Eurydice. Light explodes around her, then becomes more and more rarefied, forcing them to turn back. When they reach the earth, she says goodbye and leaves him:

I sensed that something was coming to an end. Perhaps it was in me: I made a useless, despairing effort to keep her with me...Since then I have never been up in an aeroplane.15 | orig

Most of these stories later appeared in amended or enlarged versions in other publications, the most famous contribution being a translation of part of the second chapter of James Joyce's Ulysses (the book had appeared in a very small edition in France in 1922, in English, but was banned in America until 1934 and in England until 1936).

Ivan Goll, L'Eurocoque

But perhaps the most interesting, because the most serious, was Ivan Goll's L'Eurocoque, which was also later published as a full-scale book in French and in German, and in recent years has received considerable attention in America. This was a critique of European civilization, which Goll considered to be in a terminal state of decline: The Eurocoque [euro-coccus] is a bacillus which sucks the life out of its victim, from the inside. The narrator of the story finds his exact description in the newspaper as a criminal who has attacked the Paris-Rome Express. In particular, his bright yellow gloves are mentioned, and he tries desperately to get rid of them. An elderly professor looks closely at his glove, then his hand, and says: "I've found the Eurocoque!...the phylloxera of European civilization – or, more precisely, the civilization of the west. It is the microbe which is preparing the death of this continent." He has seen buildings, books, animals eaten away from the inside, but this is the first case of the disease affecting a human being.Then he makes his chilling prophecy:

No doubt...you have been completely emptied inside. Perhaps you no longer have either heart or liver. You seem very unhappy. You no longer have any ambition, or pleasure. You are so bored, so bored! Through pure boredom you would be capable of anything, because no duty to the world, no reason, no respect, no responsibility, no faith restrain you. You have the "emptiness sickness". Look, this bandit from the Paris-Rome Express might well be you...16 | orig

This story is sufficiently significant as a critique of European civilization of the time that it is included, in translation, as an Appendix at the end of this chapter.

Astérisques

But what of Nino Frank's own writing? He was preparing a short story, but with so much of his time taken up with production concerns, this would have to wait for publication until the next issue. He also had regular paid commitments for columns in the Corriere della Sera and the Fiera letteraria. However, in this first issue of "900" he began a humorous section called 'Astérisques', which was appreciated by readers and would continue in subsequent issues. This miscellany was composed of mildly amusing aphorisms about the contemporary scene with, as highlights, brief word-portraits of men of letters in Paris.

Nino had discovered a talent for encapsulating his fellow-writers with a few words, much as caricaturists would characterize them with a few strokes of the brush, and was already building this up into a journalistic trademark. It was a talent for which he would later be known and admired, and has furnished posterity with some of the most memorable descriptions of important writers and other personalities of the twentieth century in Europe. Many modern works concerned with cultural circles in between-wars Paris draw on his descriptions: of James Joyce, for instance, Giorgio de Chirico, Blaise Cendrars, André Malraux and others, as well as his beloved Max Jacob and Pierre Mac Orlan.

At this time, in 1926, he was just beginning to develop this talent, and some of his earliest character-sketches appear in "900". The journal can still be read in academic libraries, but otherwise is almost unknown today, and is a valuable source of his early sketches. In the first issue, four of these related to authors whose stories are cited above. For the four authors he draws on different kinds of characteristics – physical or psychological – depending on his sense of what makes up their personality, and to some extent the character of the story each has contributed. Thus Mac Orlan's image is predominantly physical; Bontempelli's almost entirely other-worldly. From these very short sketches it is evident that some inside knowledge of the people and the period is required, as with visual caricatures and cartoons, and the intended audience can readily understand the allusions. For a modern reader, after a little research the characterizations open a window into the world of that time, so with each of the following descriptions a brief explanatory note is provided.

Pierre Mac Orlan

People say we are living in an age of painters: of colours or form. We build up the legend of a man from a variety of objects: we only have to list the accordeon, blood on the snow, refrains made popular by the soldiers at Mainz or in the Foreign Legion, a few obscene dolls, and we have Mac Orlan...It's an amusing game. The task of authors of portraits and especially caricatures becomes quite easy, for literary figures.

It is reasonable to place the responsibility for this state of affairs on cubism.17 | orig

Note Mac Orlan's famous accordeon appeared in his short story in this issue; he was also well-known for his marching-songs, his novels of violence among social outcasts and, to those in the know, his early pornographic writings and illustrations. His 1923 novel Malice concerned the situation in Mainz and the Rhineland generally, and the French occupying army based there, after the first World War.

Philippe Soupault

Soupault and his smile, his padded shoulders, the scent of his English cigarettes, his battles with summer, with poetry, with men. He is well hidden behind his suits, under his hat. He has the smile of Cesare Borgia. He can easily haunt your dreams. He never speaks. His smile is always terrifying.

For the benefit of those who take an interest in him, he pretends to be a writer, a literary man, the director of a journal. He is something quite different. He has found the secret of creating a twenty-fifth hour to the day – then you don't see him any more. One of these days something terrifying will happen, and he will be to blame, Soupault and his smile.18 | orig

Note Soupault insisted in dressing impeccably, to emphasise that Surrealists should not be seen as marginal anarchic characters. He favoured the English style, and in particular always smoked English cigarettes, much to the annoyance of André Breton. He and Frank had just edited a book together, Anthologie de la Nouvelle Prose Française, so they knew each other quite well, but this character-sketch expresses a sense of distance around Soupault even to his friends, and an aura of mystery and disguise echoed in his short story on Nick Carter.

Massimo Bontempelli

I can easily imagine Bontempelli giving the signal for the end of the world. With terrifying precision he would set off the loudest cataclysms, then be annoyed by the clamour around him.

I must add that I am sure he has never thought, when looking at a fly, that he could kill it with a single movement. Not that he feels any pity for flies. No. He is not aware of the existence of flies. He seems not to be aware of anything. To have abolished the outside world. To cling to the terrifying cosmogony which he hides in his own mind, and tries to make ever more perfect.19 | orig

Note The connection is clear between Bontempelli's choice of subject for his short story, and this picture of a man detached from everyday reality and, in particular, other people. Many of his other stories developed similar themes, and this kind of metaphysical exploration came to be designated "magic realism". Although evidently Frank had few illusions about Bontempelli's self-involvement, he admired him greatly and remained completely loyal to him; ironically, his outspoken defence of his master in the face of criticism would soon lead to disaster for Frank himself.

Ivan Goll

Ivan Goll, the man who sings his way through life. Impossible to miss seeing that he is German. He has a laugh the colour of the Rhine. Glasses which magnify his eyes, glinting like the lights of the Nuremberg Festival, in the night of fantasy. Impossible to miss seeing that he is French. He is full of smiles, and of market-stall irony. His eye fixes on every new spectacle, and gives him an excuse to forget how to write verses: he thinks up mysterious new theories about the universe.

My dear Robert Delaunay, keep an eye on Goll; he's the man who one of these days will steal the Eiffel Tower from you, and spirit it away.

But where?20 | orig

Note Goll was born into a French family in Alsace, where he lived his early life under German rule. With the outbreak of war in 1914 he fled to Switzerland, to avoid being conscripted to fight against France. There he was involved with Dada and early manifestations of Surrealism, and in experimental poetry forms, including cubism. Robert Delaunay, who was a friend of Goll, had established himself as the painter of the Eiffel Tower; the reference here is to Goll's long experimental poem of 1921 'Paris brennt', later published in French as 'Paris brûle', and in a German volume entitled 'Der Eiffelturm'. The Eiffel Tower, as a radio mast, had established itself as a symbol of modern invention and, in poetry, of the new experimental 'telegraphic' style.21

To summarise so far:

Bontempelli's own claims, and the short stories and pen-portraits cited above, give a very limited preview of the first issue of "900". (It can be read in full in the French original, at the British Library and other academic libraries.) It was evidently well received, and by the time it appeared preparations were well under way for the second issue. Bontempelli and his assistants were satisfied, and optimistic for the future.

However, two influential Italian writers had already shown antagonism and would continue to do so, in a vendetta which would lead to closure of the journal in its international form, and to Nino Frank's expulsion from the world of Italian letters and, effectively, total exile from Italy. The next chapter will trace, from its origins, what came to be known as the 'Polemic around "900"', and will describe the events which led to Frank forging a new career in French journalism.

APPENDIX

Ivan Goll and L'Eurocoque (my translation)

L'EUROCOQUE [THE EUROCOCCUS]

I was walking down the Avenue de l'Opéra, among the millions of other useless slobs who, all fitted out with bowler hat, raglan-sleeved wool-mixture overcoat and calf leather shoes, were obstructing this splendid road, crammed together like a spoonful of caviar on a slice of bread. I myself was only a sad grey globule, yet I clearly believed in my importance, since I was always calling on Fate with a capital 'F'. And all these beings, who passed so uncomfortably close to me, with raucous and ignoble shouts, with hostile and stupid looks, were also all day long calling on Fate to help them.

Had my curse been effective so soon? Suddenly, from a nearby street, a woman appeared who seemed to be suffering from extraordinary agitation. She was running, pointing, shouting. At the end of her right arm, like a big white bird, she brandished the evening paper, trying to sell it for 10 centimes, to make a profit of 2½ centimes per copy. To attract the attention of the deaf-and-dumb crowd, she bawled out in a tinny wail: "Attack on the Paris-Rome Express!"

I read: Three young men, one of whom bore MY name, had smuggled themselves, 130 kilometres before Paris, into a first-class coach of the famous Express: while two of them guarded the entrances, the third, I MYSELF, with a Browning automatic at the ready, visited all the compartments and calmly emptied wallets and cases. But an old officer, who had had the stupid idea of defending himself, since he still believed in divine retribution, was killed by a single little bullet. The assassin had the definite feeling that he was carrying out an act which was important even though hardly necessary. At that moment, the train slowed down because of repairs on the track, allowing the three bandits to jump and land on their feet in a field of rye glowing pink in the dawn, among the cicadas and the poppies. A terrified lark flew upwards to broadcast to the entire world the news of the attack. But before the gendarmes had picked up their sabres and helmets, the young men seized a military truck on the road, and arrived in the suburbs of Paris ahead of the Express. The last traces of the one who was ME were found in a little café in Pantin, where he had ordered a six-egg omelette and a litre of white wine: but he had disappeared without tasting them.

This is the description of the leading criminal:

Unruly hair. Sensual mouth. Hollow-eyed from gazing at the stars, during long sleepless nights. Badly-knotted tie. Dangerous appearance, like in a passport photo. Lemon-yellow gloves.

This was very precise: it was certainly me. I looked at myself in a jeweller's window and recognised myself. For the first time for ages, I felt alive. I had been vegetating in the soundproof cellars of boredom; now I realised it.

Lemon gloves. I felt my hands grow heavy and swollen as in some of Picasso's paintings. I must take them off, these dangerous gloves, but I had neither the courage nor the ability. They were sticking to my hands. The passers-by couldn't take their eyes off them. To have removed them in the street would most certainly have given me away! My hands had become the focus of attention of the whole Avenue: some people were looking at them with astonishment, others with indignation, a few with pity, but most with admiration.

What was happening? Was I about to be arrested? As I started to cross the Rue des Petits Champs the traffic policeman, noticing my lemon gloves, solemnly raised his white bâton and stopped a raspberry-red Panhard and an official Ministry of Finance car, to allow me to cross. A woman, who must have been a rich Cuban from the Ritz, turned her green eyes first to my hands, then to my eyes, and scenting the crime, signalled to me to follow her. Ordinary people stared at me, searching in my face for a resemblance, but to whom? My lemon gloves leapt out, in the middle of the Avenue de l'Opéra, and everyone was holding a copy of the newspaper which pointed to me. What, then, was this immunity I was enjoying?

At all costs, I wanted to get the gloves off my bloodstained fingers. With this aim, I entered a café, wanting to take them off in the doorway. But it was a revolving door, which turned continuously. After being swept round at a run three times, I had not yet succeeded in undoing a single glove-button. So I was forced to walk, with the damning exhibits on my hands, past rows of bald heads and tulle-bordered hats, and lips which whispered anxiously: "Unruly hair...badly-knotted tie...lemon gloves..."

Finally I reached a little marble table, right at the back of the room, backed on to a pillar. I thought I was alone. Suddenly, the head of a scholar, with grey beard and gold-rimmed glasses, came towards me from behind the pillar. The old man screwed up his left eye and took one of my hands, which I had just hidden under the table, to relieve it, finally, of the glove. He took out of the pocket of his jacket a microscope with three extending tubes, like those used by salesmen in the silk trade, put it on my glove and studied its sinews for a long time, then rolled it up and began an examination of the palm of my hand. Frozen with fear, I neither dared to remove my hand, nor to utter a word. But suddenly the man let it go, stood up and called out in a portentous voice: "The Eurococcus! I've found it!"

Nobody in a café pays attention to a man who appears to be mad. Straight away he sat down again beside me and, seeing my pallor, burst into tears and poured out his story:

"My dear Sir, you must be the most unhappy man in Paris. But one day you will be the most celebrated person of our century. You are the first European attacked by the eurococcus!

The Eurococcus, Sir, is the phylloxera of European civilization, or more precisely, the civilization of the West. It is the microbe which is preparing the death of this continent. I am a Professor of Chemistry at the University of Philadelphia, but for the last ten years I have been living in Europe and researching the microbe which is consuming you.

First of all, I found the eurococcus on the towers of Notre Dame. These are more diseased than any other historical monument, more than the Pyramids, the Strasbourg Minster, or the tombs of Prague Cemetery. Externally, not a sign: neither cracks nor holes! But the stone is blackened right through to its core, it has lost its weight and its substance, now it is no more than a sponge soaked in the smoke and tears of the city. Notre Dame, my dear Sir, no longer exists except in our imagination. It is a chimera of a construction which no longer represents faith, or God, or anything. The eurococcus has destroyed it.

A little later, I discovered the microbe on a fifteenth century quarto text which I had bought on the quays of the Seine. At first, nothing unusual appeared. The yellowed paper, spotted with brown stains, sheltered a really glorious collection of parasites: worms and aphids which, below the binding, had dug out a system of canals and shady avenues. But after long, patient work, I finally recognised the eurococcus. And the book, by one of our great classical writers, had lost almost all its significance. It had been emptied of its spirit. The sentences no longer had any meaning. The book weighed only 29 grams now, and was losing 12% of its value every year. The eurococcus, I repeat, eats away interior value and wipes out the spirit of things.

Long years passed before I was able to identify the eurococcus on an animal. You'll never guess which one taught me the ultimate lesson about our civilization: a donkey. It belonged to one of these rag-and-bone men ['chiffonniers'] who, between two and seven in the morning, do the rounds of Paris and go through the secrets of men hidden in their rubbish. Probably they are the ones who understand the greatest number of truths about life. But they keep their silence, and no-one ever sees them. They are almost invisible beneath their rags, behind the mask of wretchedness. They work like maniacs in the freezing underworld of the streets. Sometimes, tipping out buckets which are too full, they awaken frightened sleepers. Starting up in their beds, these people understand for a second that somewhere unknown forces are acting against them. But they always go back to sleep and leave their sad, vain secrets in the hands of the wretches. There was a time when, at these metaphysical hours of the night, there rose up the voice of a donkey harnessed to the cart of a rag-and-bone man, of whom it is said that his trade brought him a villa in Auteuil. This voice of wood and metal, this mournful, strident voice, expressing all the distress of the sleeping world, was as terrible as that of the condemned men in the ships and of the prophets in the gardens of the kings, the voice of reason and misfortune.

One day, after braying out into Paris the longest and most mournful cry of its life, the donkey collapsed on the asphalt. Neither whipping nor kicking would bring it back to life. And yet, it was not dead. The rag-and-bone man took it to a veterinary doctor on the Quai Bourbon, where I happened to be. And together we made this discovery: the donkey no longer consisted of anything but leather and carcass, its ears and the skin of its back being even tougher than its bridle. But inside, it no longer had lungs, or bowels, or spleen. It had been emptied, eaten away by the eurococcus...

Since then, I have succeeded in identifying the microbe. The form it takes varies with different objects and beings. I had never yet found it on a man. And now, here it is on your hand! The human eurococcus. Let me embrace you, my dear Sir. You are rendering an outstanding service to humanity.

No doubt, in the same way as stones, books and donkeys, you have been completely emptied inside. Perhaps you no longer have either heart or liver. You seem very unhappy. You no longer have any ambition, or any pleasure. You are so bored, so bored! Through pure boredom you would be capable of anything at all, because no duty to the world, no reason, no respect, no responsibility, no faith restrain you. You have the "emptiness sickness". Look, this bandit from the Paris-Rome Express might well be you..."

All translations from European texts are my own.

[CLICK HERE to open notes in a new window]

Notes

1Benjamin Crémieux, 'Italo Svevo', Le Navire d'argent, no.9, 1.2.26, p.23.

2Nino Frank, 'A Milan: Un découverte', Nouvelles littéraires, 20.2.26, p.6

3Alvaro, Bontempelli, Frank, Lettere a "900" (Rome: Bulzoni Editore, 1985), letter no.2 from Frank to Bontempelli, 1.3.26, p.192.

4Nino Frank, 'Le compteur de la rue d'Alésia', Le Bruit parmi le vent (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1968), pp.265-267. Note: The 'Vert-Galant' is the statue of Henri IV at the western tip of the Île de la Cité, and the Morgue stood at the opposite, eastern, tip, now the site of the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation. The shape of the Île is often compared to that of a ship.

5See Bernard Baritaud, Pierre Mac Orlan: Sa vie, son temps (Geneva: Droz, 1992), pp.169-171.

6Lettere a "900", letter no.3 from Frank to Bontempelli, 7.5.26, pp.194-197.

7Lettere a "900", letter no.35 from Bontempelli to Frank, 19.10.26, p.120.

8Lettere a "900", letter no.16 from Alvaro to Frank, 5.11.26, p.26.

9Lettere a "900", letter no.28 from Frank to Bontempelli, 6.11.26, p.244.

10"900", Cahier d'Automne, October 1926.

11Benjamin Crémieux, "900", Nouvelle Revue Française, December 1926, p.770.

12"900", p.26.

13"900", p.66.

14"900", p.106.

15"900", pp.18-19.

16"900", pp.135-138.

17"900", p.186.

18"900", p.185.

19"900", p.186.

20"900", p.185.

21For further information on Ivan Goll, with the English translation of his short story, see the entry 'Ivan Goll and L'Eurocoque' on this website, under the Menu heading 'Translations from French'.

Original quotations from which translations taken

(numbers match relevant endnotes)

2L'Esame s'insurge contre eux, affirme avoir découvert Svevo depuis trois mois...tandis que Crémieux dénie toute originalité aux deux premiers livres de Svevo, et leur oppose le troisième, roman de psychanalyse caricaturale, l'Esame affirme que Svevo ne vaut que par ses deux premiers livres, assez flaubertiens.

3Dacché sono diventato, a Parigi, uomo d'azione, mi sembra di crepare, qui, con tutti morti e morti. Allora lavoro continuamente. Faccio due romanzi e una commedia oltre a 12 altre cose.

4Je vivais avec un ange...Qu'est-il de plus enivrant que de montrer Paris et sa nuit à la femme qu'on aime? Tout nous tentait, dans les pauvres éclairages du temps, mais surtout la Seine, depuis le Vert-Galant jusqu'à la Morgue sise encore à la poupe de la nef: mais, bientôt, d'invisibles filins nous ramenaient vers la masse mystérieuse des vieilles pierres de Cluny...nous n'étions qu'un couple d'amoureux comme les autres.

6Il 900 è un'idea meravigliosa e una delle tue più belle invenzioni, hai avuto ragione di capire che ne sarei stato entusiasta. Come avrai visto dalle Nouvelles littéraires d'oggi, e come vedrai (ti spedirò) da ritagli della Gazette du Franc, dell'Intrans, di Paris-Soir, ecc. provvedo a strombazzare la notizia ai quattro venti.

...Aragon non è adatto per dirigere a Parigi, poiché è intollerante. Ho pensato che Mac Orlan era l'unico adatto – anzitutto per il nome, poi per le molte amicizie che ha con editori ecc., infine poiché non è affatto intollerante. Glien'ho parlato, accetta, approva, s'è entusiasmato anche lui. E per mio mezzo ti spedisce questi consigli (mi servirà molto anche per aver manoscritti, me l'ha già proposto).

7Da ultimo Crès vien fuori con la condizione che la spedizione (e rispedizione poi delle invendute) sia a nostro carico, il che, visto che prende il 50% (!) anche sulle copie in deposito, è un'enormità.

8In Italia la rivista ha un grandissimo successo e se ne parla e se ne scrive molto, oltre a vendersi magnificamente.

9Guarda che qui tutti parlano di "900". E mi si chiede quanto abbiamo speso in pubblicita! Nessuna rivista è mai nata tanto bene. Vediamo di portarla bene in porto.

10 – de construire à nouveau et de mettre au point un monde réel en dehors de l'homme

– la vie, même la plus quotidienne et la plus banale, vue comme une aventure miraculeuse, comme un risque perpétuel

– c'est déplacer un coin de la surface de la réalité pour vous faire voir la réalité plus profonde.

11M. Bontempelli prône un réalisme imaginatif, le récit ou l'évocation d'un monde imaginaire, mais objectivement décrit, un art assez proche en somme de celui de Max Jacob, de Mac Orlan, de Ramòn Gomez de la Serna, et dans un certain sens d'Arioste.

12 vers l'île de l'aventure: une île ronde de cinq cents couverts, recouverte d'une nappe blanche, où la boisson, le café et les liqueurs étaient compris dans le repas qui nous attendait.

13Un nègre la main bandée, acheta un journal et donna au marchand un billet de cents francs. "Gardez la monnaie" fit-il.

14Personne ne tirait certainement au lièvre, par une nuit pareille. Il y avait donc encore en tout cas des gens vivants en ce monde: des gens qui se tiraient dessus.

15Je sentis que quelque chose finissait. C'était peut-être en moi: je fis un effort inutile et désespéré pour la retenir...je ne suis plus remonté en aéroplane.

16L'Eurocoque! Je l'ai! ... c'est le phylloxéra de la civilisation européenne, ou, pour être plus exact, occidentale. C'est le microbe qui prépare la mort de ce continent.

Sans doute...êtes-vous complètement vidé intérieurement. Vous n'avez peut-être plus de cœur ni de foie. Vous semblez être bien malheureux. Vous n'avez plus aucune ambition, plus aucun plaisir. Vous vous ennuyez, vous vous ennuyez! Par pur ennui, vous seriez capable de n'importe quoi, puisque aucun devoir au monde, aucune raison, aucun respect, aucune responsabilité, aucune foi ne vous tiennent. Vous avez la "maladie du vide". Tenez, vous pourriez être ce bandit du rapide Paris-Rome...

17Nous en sommes, à ce qu'on dit, à une époque de peintres: époque des couleurs ou plastique. La légende résulte maintenant d'une complexité d'objets: citons l'accordéon, le sang sur la neige, certaines scies popularisées par les soldats à Mayence ou dans le bled, quelques poupées obscènes, et on aura Mac Orlan...Le jeu est amusant. La tâche des auteurs de portraits et surtout de caricatures devient assez facile, avec les hommes de lettres.

Il est loisible de donner la responsabilité de cet état de choses au cubisme.

18Soupault et son sourire, ses épaules carrées, le parfum de son tabac anglais, sa vigueur contre l'été, contre la poésie, contre les hommes. Il est bien caché dans ses costumes, sous son chapeau. Il a le sourire de César Borgia. On le voit en rêve très facilement. Il ne parle jamais. Son sourire est toujours effrayant.

Pour ceux qui l'observent, il feint d'être écrivain, homme de lettres, directeur de revue. Il est autre chose. Il a trouvé le secret de créer la vingt-cinquième heure de la journée. Alors on le voit plus.

Un jour ou l'autre, il se passera quelque chose d'effrayant, et c'en sera lui le responsable, lui et son sourire.

19Je vois assez bien Bontempelli donnant le signal de la fin du monde. Il déclencherait avec une précision effrayante les cataclysmes les plus bruyants, tout en étant incommodé par la clameur.

J'ajoute qu'il ne doit avoir jamais pensé, en regardant une mouche, qu'il est possible de la tuer par un geste quelconque. Non pas qu'il ait pitié des mouches. Non. Mais il ne s'aperçoit pas de l'existence des mouches. Il a l'air de ne s'apercevoir de rien. D'avoir aboli le monde extérieur. De s'en tenir à l'effrayante cosmogonie qu'il cache dans son esprit et qu'il essaye de rendre toujours plus parfaite.

20Ivan Goll, l'homme qui chante tout le long de sa vie. Impossible de ne pas voir qu'il est allemand. Il a un rire couleur du Rhin. Des lunettes qui agrandissent l'œil, clignant comme les lumières de Nuremberg, dans la nuit de la fantaisie. Impossible de ne pas voir qu'il est français. Il est plein de sourires, d'ironie foraine. Son œil se fixe sur tout spectacle, il en profite pour oublier la versification: il crée de mystérieux projets de cosmogonies nouvelles.

Mon cher Robert Delaunay, surveillez Goll; c'est l'homme qui un jour ou l'autre vous volera la tour Eiffel pour l'emporter.

Où?